Impact Factor

ISSN: 1837-9664

J Cancer 2016; 7(6):687-693. doi:10.7150/jca.14819 This issue Cite

Review

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors for the Elderly

1. Medical Clinic I, ''Fuerth'' Hospital, University of Erlangen, Fuerth, Germany

2. Pulmonary Oncology Unit, “G. Papanikolaou” General Hospital, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

3. Oncology Department, “Interbalkan” European Medical Center, Thessaloniki, Greece

4. Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Sheikh Zayed Cardiovascular & Critical Care Tower, Baltimore, U.S.A

5. Thoracic Surgery Department, “Saint Luke” Private Hospital, Panorama, Thessaloniki, Greece

6. Ear, Nose and Throat Department, “Saint Luke” Private Hospital, Panorama, Thessaloniki, Greece

7. Research Laboratory and International Collaboration, Bon Secours Cancer Institute, VA, USA

8. Department of Interventional Pneumology, Ruhrlandklinik, University Hospital Essen, University of Essen-Duisburg, Tueschener Weg 40, 45239 Essen, Germany

9. Nuclear Medicine Department, University General Hospital of Alexandroupolis, Democritus University of Thrace, Alexandroupolis, Thrace, Greece

Received 2015-12-27; Accepted 2016-2-13; Published 2016-3-21

Abstract

Until few years ago non-specific cytotoxic agents were considered the tip of the arrow as first line treatment for lung cancer. However; age > 75 was considered a major drawback for this kind of therapy. Few exceptions were made by doctors based on the performance status of the patient. The side effects of these agents are still severe for several patients. In the recent years further investigation of the cancer genome has led to targeted therapies. There have been numerous publications regarding novel agents such as; erlotinib, gefitinib and afatinib. In specific populations these agents have demonstrated higher efficiency and this observation is explained by the overexpression of the EGFR pathway in these populations. We suggest that TKIs should administered in the elderly, and with the word elderly we propose the age of 75. The treating medical doctor has to evaluate the performance status of a patient and decide the best treatment in several cases indifferent of the age. TKIs in most studies presented safety and efficiency and of course dose modification should be made when necessary. Comorbidities should be considered in any case especially in this group of patients and the treating physician should act accordingly.

Keywords: erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib, targeted therapies, elderly

Introduction

Lung cancer is considered the second most frequent cancer for men after prostate cancer and breast cancer for women. [1] Non-specific cytotoxic agents are currently used for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC).[2-4] However; side effects are the reason for some patients to postpone their treatment and in some cases to be hospitalized increasing the cost of treatment.[5] In the recent years targeted therapies have emerged and based on the genome of cancer specific oral agents are being administered. [2] Epidermal growth factor receptor status and anaplastic lymphoma kinase status are the two most investigated pathways regarding adenocarcinoma. [6-8] Erlotinib, gefinitib, afatinib and crizotinib are the most frequently used targeted agents.[7, 9] Erlotinib, gefinitib and afatinib have presented superiority in terms of overall survival and disease control when compared to doublet chemotherapy agents in a specific group of patients.[10] However; resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors has been observed and therefore new or alternative treatment approaches are being investigated.[11] These agents are considered safer in the sense that the patients have less side effects, however; they still have side effects which in some cases are dose dependent and directly compared with the positive disease control.[12] Regarding SCLC chemotherapy is still the considered the best first line treatment, however; several novel therapies are being investigated.[13-16] The role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors as neo-adjuvant or adjuvant treatment is still under investigation. One observation has to be taken into serious consideration that if chemotherapy is administered in EGFR positive patients as neo-adjuvant treatment then the mutation status will change along with the gene status of several other involved pathways with an unknown treatment effect in the future if treatment will become necessary (disease relapse). [17] In the study by Spaans JN et al. [18] it is suggested that there are no clear evidence that a patient should receive neo-adjuvant tyrosine kinase inhibitors for early stage NSCLC, however; there are evidence that patients will benefit from this oral drug administration. In the case presented by Funakoshi Y et al. [19] a patient received gefinitib as neo-adjuvant treatment, downstaging of the disease was observed and the patient underwent pneumonectomy. In the study by Li N et al. [20] it is suggested that as adjuvant treatment gefinitib can be administered with or without other chemotherapy agents. In the editorial by Martinez P et al. [21] it is suggested that tyrosine kinase inhibitors could be used as adjuvant treatment, however; because of the few trials which have small patient samples and with unselected patients more studies are still needed. Regarding afatinib a meta-analysis presented data where this drug could be considered as more toxic than erlotinib and gefitinib.[7] There are no data regarding afatinib as neo-adjuvant treatment, however; regarding adjuvant treatment there is one study by Burtness B et al. [22], which has not investigated lung cancer, but head and neck cancer. Maybe this study could be used for further investigation of afatinib as adjuvant treatment for NSCLC. There is one group of patients that tyrosine kinase inhibitors are still under investigation whether they would benefit or not. The “elderly” if one could set the age for this group of patients it would probably be >75 years of age which is more or less recognized by the international medical community the cut off age that a patient should receive chemotherapy. Although in several patient cases an individualized approach is necessary if the patient has could performance status. The elderly are not considered could candidates for trials since they tend not to complete them due to side effects.[23]

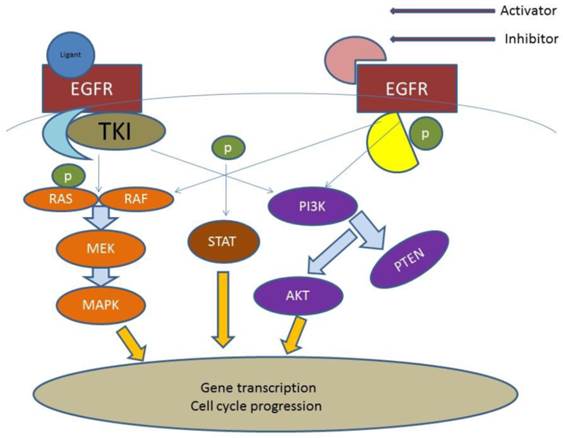

EGFR; Epidermal Growth Factor, AKT; kinase-interacting protein1, PTEN; Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate 3-phosphatase, PI3K; Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinases, PI 3-kinases, PI(3)Ks, RAS; Ras superfamily of proteins, which are all related in 3D structure and regulate diverse cell behaviours, RAF; Raf kinases (more avidly C-Raf than B-Raf), MAPK/ERK; extracellular signal-regulated kinases , TKI; Tyrosine kinase inhibitor, STAT; Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription. MEK; mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase enzymes MEK1 and/or MEK2.

In the current mini review we will focus on the group of patients >70 years of age. We will present up to date studies and comment on the targeted treatment for this group of patients. (Figure 1)

Search methods

We performed an electronic article search through PubMed, Google Scholar, Medscape and Scopus databases, using combinations of the following keywords: tyrosine kinase inhobitors, erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib, and combination of these words with the word elderly. All types of articles (randomised controlled trials, clinical observational cohort studies, review articles, case reports) were included. Selected references from identified articles were searched for further consideration indifferent of the language.

Tyrosine Kinase in the elderly (TKIs)

Erlotinib

In the study by Yoshioka H. et al. [24] a very well designed study the patients and adverse effects of the TKIs were stratified according to age in three different groups as follows: a) <75, b) 75 -84 and c) 85≥. The incidence of interstitial lung disease (ILD) (all grades) was 4.2% (<75 years), 5.1% (75-84 years), and 3.4% (≥85 years). The mortality rate due to ILD was ≤1.7% in all age groups. Other toxicities (including rash) were similar between age groups. Therefore it was concluded that erlotinib is safe and efficient for patients >75 years of age. In the study by Kurishima K et al. [25] patients receiving erlotinib were divided into two groups: a) ≤75 and b) >75. It was observed that adverse effects were the same in both groups and the overall survival did not differ between the elderly and younger groups (median, 170 days; 95% CI: 142‑239 days vs. median, 146 days; 95% CI: 114‑185 days, respectively) (P=0.7642). Therefore it was concluded that targeted treatment is safe and efficient for this group of patients. In the study by Jackman DM. et al. [26] patients of >70 years of age were included and erlotinib was administered. The most common toxicities were acneiform rash (79%) and diarrhea (69%). Four patients developed interstitial lung disease of grade 3 or higher, with one treatment-related death. It was concluded that Erlotinib merits consideration for further investigation as a first-line therapeutic option in elderly patients. In the study by Chen YM. Et al. [27] patients of ≥ 70 years of age were included and received either erlotinib or vinorelbine. Toxicities were generally mild in both groups. Overall survival was longer for EGFR-mutated patients than for EGFR wild-type patients (p < 0.0001). It was concluded that erlotinib is highly effective compared with oral vinorelbine in elderly, chemonaive, Taiwanese patients with NSCLC. EGFR-mutated patients had better survival than those with EGFR wild-type disease, regardless of the treatment received. In the study by Wheatley-Price P. et al. [28] two groups were formed: a) <70 years of age and b) >70 years of age (elderly). Response rates were similar between age groups. Elderly patients, compared with young patients, had significantly more overall and severe (grade 3 and 4) toxicity (35% v 18%; P _ .001), were more likely to discontinue treatment as a result of treatment-related toxicity (12% v 3%; P _ .0001), and had lower relative dose-intensity (64% v 82% received _ 90% planned dose; P _ .001). It was concluded that Elderly patients treated with erlotinib gain similar survival and QOL benefits as younger patients but experience greater toxicity. In the study by Platania M. et al. [29] patients of ≥70 years of age were included and erlotinib was administered. Skin rash was the most common side effect (67%). Grade 3-4 adverse events were observed in 16 cases (37%). It was concluded that the use of erlotinib after chemotherapy failure in an unselected elderly population affected by NSCLC showed moderate efficacy and a moderate safety profile and therefore erlotinib represents a valid option in this setting. (Table 1)

Gefitinib

In the study by Morikawa N. et al. [30] patients of >70 years of age were included. It was observed that elevation of aspartate transaminase and/or alanine transaminase (18.3%) was the most common adverse event, and one treatment-related death (pneumonitis) occurred. It was concluded that first-line gefitinib is efficacious with acceptable toxicity in relatively fit elderly patients with advanced NSCLC harboring an EGFR mutation. In the study by Des Guetz G. et al. [31] patients were divided in two major groups: a) <70 years of age and b) >70 years of age. Patients were subdivided into three groups receiving three different drugs (gefitinib; gemcitabine; and docetaxel). It was observed that older patients had a decreased risk of progression/death compared to younger patients. Single-agent chemotherapy can be considered for patients aged ≥70years with a PS of 2. In the study by Takahashi K. et al. [32] patients between 72-90 years of age were included specifically to access the safety and effectiveness of gefitinib in the elderly (median age was 79.5 years). The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung Cancer Subscale (FACT-LCS) scores improved significantly 4 weeks after the initiation of gefitinib (P = 0.037) and maintained favorably over a 12-week assessment period. The most common adverse events were rash and liver dysfunction. Although Grade 1 pneumonitis developed in one patient, no treatment-related death was observed. It was observed that first-line gefitinib therapy is effective and feasible for elderly patients harboring EGFR mutation, and improves disease-related symptoms, especially pulmonary symptoms like shortness of breath and cough. In the study by Inoue A. et al. [33] patients >74 years of age were included with poor performance status and with the administration of gefitinib no treatment-related deaths were observed. Gefitinib was safe and efficient. In the study by Maemondo M. et al. [34] patients of >75 years of age were included and gefitinib was administered. The common adverse events were rash, diarrhea, and liver dysfunction. One treatment-related death because of interstitial lung disease occurred. This was the first study that verified safety and efficacy of first-line treatment with gefitinib in elderly patients having advanced NSCLC with EGFR mutation. It was concluded that due to its strong antitumor activity and mild toxicity, first-line gefitinib may be preferable to standard chemotherapy for this population. (Table 2)

Erlotinb/Gefitinb

In the study by Nakao M. et al. [35] patients of ≥80 years of age were included and the TKIs gefitinib and erlotinib were administered. It was observed that the administration of these agents to this group of age was acceptable, however; the authors suggest that a careful dose selection according to the overall medical condition should be made. (Table 3)

Erlotinib in the elderly

| Author | Patients | Adverse effects | Efficiency | Proposal | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yoshioka H. et al. | (<75 years, n = 7848; 75-84 years,n = 1911; ≥85 years, n = 148 | incidence of ILD (all grades) was4.2% (<75 years), 5.1% (75-84 years), and 3.4% (≥85 years), rash was similar between age groups | median PFS was65 days (95% confidence interval [CI], 62-68) for patients aged <75 years, 74 days (95% CI, 69-82) forpatients aged 75-84 years, and 72 days (95% CI, 56-93) for patients aged ≥85 years. | Erlotinib could be considered for elderly patients with recurrent/advancedNSCLC | 24 |

| KURISHIMA K. et al. | (≥75 years, n=74) and a younger group of patients (<75 years, n=233) | adverse events did not differ in incidence between the groups and were manageable, regardless of age | The overall survival did not differ between the elderly and younger groups (median, 170 days; 95% CI: 142‑239 days vs. median, 146 days; 95% CI: 114‑185 days, respectively) (P=0.7642) | Among the NSCLC patients receiving erlotinib treatment, the outcomes of the elderly (≥75 years) and younger (<75 years) groups of patients were similar in our population‑based observational study | 25 |

| Jackman DM. et al. | phase II, multicenter, open-label study of chemotherapy-naı¨ve patients with non-smallcell lung cancer (NSCLC) and age _ 70 years who were treated with erlotinib and evaluated to determine the median, 1-year, and 2-year survival | The most common toxicities were acneiform rash (79%) and diarrhea (69%). Four patients developed interstitial lung disease of grade 3 or higher, with one treatment-related death | eight partial responses (10%), and an additional 33 patients (41%) had stable disease for 2 months or longer. The median TTP was 3.5 months (95% CI, 2.0 to 5.5 months). The median survival time was 10.9 months (95% CI, 7.8 to 14.6 months). The 1- and 2- year survival rates were 46% and 19%, respectively | Erlotinib merits consideration for further investigation as a first-line therapeutic option in elderly patients | 26 |

| Wheatley-Price P. et al. | two age groups: _ 70 years (elderly) or less than 70 years (young) | Elderly patients, compared with young patients, had significantly more overall and severe (grade 3 and 4) toxicity (35% v 18%; P _ .001), were more likely to discontinue treatment as a result of treatment-related toxicity (12% v 3%; P _ .0001), and had lower relative dose-intensity (64% v 82% received _ 90% planned dose; P _ .001 | no significant difference between age groups randomly assigned to erlotinib or placebo in progression-free survival (elderly: 3.0 v 2.1 months; hazard ratio [HR] _ 0.63; 95% CI, 0.44 to 0.90; P _ .009; young: 2.1 v 1.8 months; HR _ 0.64; 95% CI, 0.53 to 0.76; P _ .0001; interaction, P_.77) or OS (elderly: 7.6 v 5.0 months; HR_0.92; 95% CI, 0.64 to 1.34; P_.67; young: 6.4 v 4.7 months; HR _ 0.73; 95% CI, 0.61 to 0.89; P _ .0014; interaction, P _ .31). | Elderly patients treated with erlotinib gain similar survival and QOL benefits as younger patients but experience greater toxicity | 28 |

| Platania M. et al. | group of pretreated elderly metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients admitted to our institution and treated with erlotinib at standard daily/dose (≥70 years of age) | Skin rash was the most common side effect (67%). Grade 3-4 adverse events were observed in 16 cases (37%). | The median overall survival and the median progression-free survival were 8.4 months (CI 95%: 0.7- 43.6) and 3 months (CI 95%: 0.4-28.4), respectively. Patients with adenocarcinoma achieved the best disease control rate (p=0.027), while not/former smokers showed a better response (p=0.069) | factors such as biological information, comorbidities and concomitant medications need to be carefully take into consideration in this particular subset of cancer patients | 29 |

| Chen YM. et al. | Chemonaive Taiwanese patients aged 70 years or older who had advanced NSCLC were randomized to receive either oral erlotinib 150 mg (E) daily or oral vinorelbine 60 mg/m2 (V) on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks | Toxicities were generally mild in both groups | Objective response rates were 22.8% (13 of 57) in E and 8.9% (5 of 56) in V (p _ 0.0388). Median progression-free survival (PFS) was 4.57 months in E and 2.53 months in V (p _ 0.0287), with an 80.6% increase in median PFS for E compared with V. Median survival time was 11.67 months in E and 9.3 months in V (p _ 0.6975) | Erlotinib is highly effective compared with oral vinorelbine in elderly, chemonaive, Taiwanese patients with NSCLC. EGFR-mutated patients had better survival than those with EGFR wild-type disease, regardless of the treatment received | 27 |

Gefinitib in the elderly

| Author | Patients | Adverse effects | Efficiency | Proposal | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morikawa M. et al. | pooled data from one Phase III and two Phase II studies of 71 patients aged ≥ 70 years with a performance status of 0 - 2 | Elevation of aspartate transaminase and/or alanine transaminase (18.3%) was the most common adverse event, and one treatment-related death (pneumonitis) occurred. Time to 9.1% deterioration in the QoL domains of pain and dyspnea, anxiety, and daily functioning was similar between the two age groups | Median PFS (14.3 vs 5.7 months, p < 0.001) and overall RR (73.2 vs 26.5%, p < 0.001) in the gefitinib group were superior to those in the standard chemotherapy group, whereas median OS was not significantly different (30.8 vs 26.4 months, p = 0.42) | First-line gefitinib is efficacious with acceptable toxicity in relatively fit elderly patients with advanced NSCLC harboring an EGFR mutation | 30 |

| Des Guetz G. et al. | two subgroups aged <70 years (younger, n = 56) and ≥70 years (older, n = 71) | Toxicity did not differ between younger and older patients | Progression-free survival (PFS) was 1.4 months (95% CI: 1.1-1.9) for younger compared to 2.3 months (95% CI: 2.1-2.9) for elderly patients. Overall survival (OS) was 2.0 months (95% CI: 1.5-2.4) and 3.7 months (95% CI: 2.4-4.8), respectively | Older patients had a decreased risk of progression/death compared to younger patients. Single-agent chemotherapy can be considered for patients aged ≥70 years with a PS of 2 | 31 |

| Takahashi K. et al. | Chemotherapy-naοve patients aged 70 years or older with stage IIIB or IV NSCLC harboring EGFR-activating mutation were enrolled and treated with 250 mg of gefitinib daily until disease progression | The most common adverse events were rash and liver dysfunction. Although Grade 1 pneumonitis developed in one patient, no treatment-related death was observed | Overall response rate was 70 % (95 % CI 45.7-88.1 %), and the disease control rate was 90 % (95 % CI 68.3-98.7 %). The median progression- free survival and overall survival time were 10.0 and 26.4 months, respectively | First-line gefitinib therapy is effective and feasible for elderly patients harboring EGFR mutation, and improves disease-related symptoms, especially pulmonary symptoms like shortness of breath and cough | 32 |

| Maemondo M et al. | Chemotherapy-naive patients aged 75 years or older with performance status 0 to 1 and advanced NSCLC harboring EGFR mutations, as determined by the peptide nucleic acid-locked nucleic acid polymerase chain reaction clamp method, were enrolled. The enrolled patients received 250 mg/day of gefitinib orally | The common adverse events were rash, diarrhea, and liver dysfunction. One treatment-related death because of interstitial lung disease occurred | The overall response rate was 74% (95% confidence interval, 58%-91%), and the disease control rate was 90%. The median progression-free survival was 12.3 months | Considering its strong antitumor activity and mild toxicity, first-line gefitinib may be preferable to standard chemotherapy for this population | 34 |

| Because there previously has been no standard treatment for these patients with short life expectancy other than best supportive care, examination of EGFR mutations as a biomarker is recommended in this patient population | |||||

| Inoue A. et al. | Oncology Group PS 3 to 4, 75 to 79 years of age with PS 2 to 4, and _ 80 years of age with PS 1 to 4) who had EGFR mutations were enrolled and received gefitinib (250 mg/d) alone | No treatment-related deaths were observed | The overall response rate was 66% (90% CI, 51% to 80%), and the disease control rate was 90%. PS improvement rate was 79% (P _ .00005); in particular, 68% of the 22 patients improved from _ PS 3 at baseline to _ PS 1. The median progression-free survival, median survival time, and 1-year survival rate were 6.5 months, 17.8 months, and 63%, respectively | Because there previously has been no standard treatment for these patients with short life expectancy other than best supportive care, examination of EGFR mutations as a biomarker is recommended in this patient population | 33 |

Erlotinib/Gefitinib in the elderly

| Author | Patients | Adverse effects | Efficiency | Proposal | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nakao M. et al. | This retrospective study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of EGFR‑TKIs for NSCLC patients aged ≥80 years. | Adverse events ≥grade 2 were as follows: skin toxicities, 12 patients; liver function test abnormalities, 7 patients; anorexia, 3 patients; and diarrhea, 2 patients. Dose reduction of EGFR‑TKIs due to adverse events was required in 15 patients (71.4%) | In total, 14 (66.7%), 5 (23.8%) and 2 patients (9.5%) displayed partial response, stable disease and progressive disease, respectively. The median progression‑free survival was 182 days, whereas the median overall survival was 371 days | Although gefitinib and erlotinib therapy may be beneficial in patients aged ≥80 years, EGFR‑TKI dose modification may be necessary according to the overall medical condition of elderly patients | 35 |

Discussion

Possibly a new group of patients including >75 years of age could be considered in the treatment of lung cancer since targeted treatment with TKIs surpass the major obstacle of chemotherapy side effects. In the study by Costa GJ et al. [36] patients were divided in two groups: a) <70 years of age and b) > 70 years of age. Platinum based chemotherapy was administered and the results indicated that “elderly patients” >70 years of age for the first two years of drug administration had the same side effects when compared to patients of <70 and treatment was well tolerated. Therefore it was proposed that “elderly patients” > 70 years of age could choose non-specific cytotoxic agents for treatment of NSCLC. In the study by Yellen SB. Et al. [37] patients were divided into two groups: a) <65 years of age and b) > 65. It was observed that most patients in group b were willing to have chemotherapy treatment, however; when they were asked to choose between survival and quality of life, most of them chose quality of life. In all the studies included patients were harboring epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations. In the study by Wheatley-Price P. et al. [28] severe toxicity was observed in a number of patients and therefore dose modification was required. In the study by Bai H. et al. [38] gastric bleeding was observed by the administration of both erlotinib and gefitinib. Erlotinib is known to cause gastric bleeding and it is dose dependent. A major issue that we identified during our search firstly is that there is no clear definition which patient is considered “elder”. In the U.S.A elderly were considered mostly patients >70, while in Europe >75 years of age. Secondly very few studies were designed especially with the purpose to identify whether TKIs should be definitely administered to the elderly. One of the reasons is that in general studies conducted with patients more than 70 years of age are difficult to recruit and maintain the follow up of the patients.[23] Thirdly in a number of studies the first line treatment of choice was chemotherapy and the second line was a TKI. However; as previously presented the status of the EGFR changes after chemotherapy, therefore we need more studies without previously treated elderly.[17] Moreover; there are no data concerning afatinib and the elderly patients. Afatinib is a very new drug in the market and current data indicate that is slightly more toxic than erlotinib and gefitinib.[39] Based on the current information we suggest that TKIs should administered in the elderly, and with the word elderly we propose the age of 75. The treating medical doctor has to evaluate the performance status of a patient and decide the best treatment in several cases indifferent of the age. TKIs in most studies presented safety and efficiency and of course dose modification should be made when necessary. Comorbidities should be considered in any case especially in this group of patients and the treating physician should act accordingly.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Boffetta P. Epidemiology of environmental and occupational cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:6392-403 doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1207715

2. Domvri K, Zarogoulidis P, Darwiche K, Browning RF, Li Q, Turner JF. et al. Molecular Targeted Drugs and Biomarkers in NSCLC, the Evolving Role of Individualized Therapy. Journal of Cancer. 2013;4:736-54 doi:10.7150/jca.7734

3. Zarogoulidis K, Latsios D, Porpodis K, Zarogoulidis P, Darwiche K, Antoniou N. et al. New dilemmas in small-cell lung cancer TNM clinical staging. OncoTargets and therapy. 2013;6:539-47 doi:10.2147/OTT.S44201

4. Kallianos A, Rapti A, Zarogoulidis P, Tsakiridis K, Mpakas A, Katsikogiannis N. et al. Therapeutic procedure in small cell lung cancer. Journal of thoracic disease. 2013;5(Suppl 4):S420-4 doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.09.16

5. Zarogoulidou V, Panagopoulou E, Papakosta D, Petridis D, Porpodis K, Zarogoulidis K. et al. Estimating the direct and indirect costs of lung cancer: a prospective analysis in a Greek University Pulmonary Department. Journal of thoracic disease. 2015;7:S12-9 doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.01.57

6. Iacono D, Chiari R, Metro G, Bennati C, Bellezza G, Cenci M. et al. Future options for ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Lung cancer. 2015;87:211-9 doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.12.017

7. Burotto M, Manasanch EE, Wilkerson J, Fojo T. Gefitinib and Erlotinib in Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Toxicity and Efficacy of Randomized Clinical Trials. The oncologist. 2015 doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0154

8. Somasundaram A, Socinski MA, Burns TF. Personalized treatment of EGFR mutant and ALK-positive patients in NSCLC. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2014;15:2693-708 doi:10.1517/14656566.2014.971013

9. Gainor J. O10.1Next generation ALK inhibitors and mechanisms of resistance to therapy. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2015;26(Suppl 2):ii14. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdv088.1

10. Hasegawa Y, Ando M, Maemondo M, Yamamoto S, Isa S, Saka H. et al. The Role of Smoking Status on the Progression-Free Survival of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Harboring Activating Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Mutations Receiving First-Line EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Versus Platinum Doublet Chemotherapy: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Randomized Trials. The oncologist. 2015;20:307-15 doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0285

11. Matikas A, Mistriotis D, Georgoulias V, Kotsakis A. Current and Future Approaches in the Management of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients With Resistance to EGFR TKIs. Clinical lung cancer. 2015 doi:10.1016/j.cllc.2014.12.013

12. de Marinis F, Vergnenegre A, Passaro A, Dubos-Arvis C, Carcereny E, Drozdowskyj A. et al. Erlotinib-associated rash in patients with EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer treated in the EURTAC trial. Future oncology. 2015;11:421-9 doi:10.2217/fon.14.269

13. Zarogoulidis K, Eleftheriadou E, Kontakiotis T, Gerasimou G, Zarogoulidis P, Sapardanis I. et al. Long acting somatostatin analogues in combination to antineoplastic agents in the treatment of small cell lung cancer patients. Lung cancer. 2012;76:84-8 doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.09.014

14. Zarogoulidis K, Ziogas E, Boutsikou E, Zarogoulidis P, Darwiche K, Kontakiotis T. et al. Immunomodifiers in combination with conventional chemotherapy in small cell lung cancer: a phase II, randomized study. Drug design, development and therapy. 2013;7:611-7 doi:10.2147/DDDT.S43184

15. Zarogoulidis K, Boutsikou E, Zarogoulidis P, Darwiche K, Freitag L, Porpodis K. et al. The role of second-line chemotherapy in small cell lung cancer: a retrospective analysis. OncoTargets and therapy. 2013;6:1493-500 doi:10.2147/OTT.S52330

16. Domvri K, Bougiouklis D, Zarogoulidis P, Porpodis K, Xristoforidis M, Liaka A. et al. Could Somatostatin Enhance the Outcomes of Chemotherapeutic Treatment in SCLC? Journal of Cancer. 2015;6:360-6 doi:10.7150/jca.11308

17. Wang S, An T, Duan J, Zhang L, Wu M, Zhou Q. et al. Alterations in EGFR and related genes following neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in Chinese patients with non-small cell lung cancer. PloS one. 2013;8:e51021. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051021

18. Spaans JN, Goss GD. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in early-stage nonsmall cell lung cancer. Current opinion in oncology. 2015;27:102-7 doi:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000163

19. Funakoshi Y, Takeuchi Y, Maeda H. Pneumonectomy after response to gefitinib treatment for lung adenocarcinoma. Asian cardiovascular & thoracic annals. 2013;21:482-4 doi:10.1177/0218492312462834

20. Li N, Ou W, Ye X, Sun HB, Zhang L, Fang Q. et al. Pemetrexed-carboplatin adjuvant chemotherapy with or without gefitinib in resected stage IIIA-N2 non-small cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations: a randomized, phase II study. Annals of surgical oncology. 2014;21:2091-6 doi:10.1245/s10434-014-3586-9

21. Martinez P, Martinez-Marti A, Navarro A, Cedres S, Felip E. Molecular targeted therapy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: will it increase the cure rate? Lung cancer. 2014;84:97-100 doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.01.018

22. Burtness B, Bourhis JP, Vermorken JB, Harrington KJ, Cohen EE. Afatinib versus placebo as adjuvant therapy after chemoradiation in a double-blind, phase III study (LUX-Head & Neck 2) in patients with primary unresected, clinically intermediate-to-high-risk head and neck cancer: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:469. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-15-469

23. Rowe J, Patel S, Mazo-Canola M, Parra A, Goros M, Michalek J. et al. An evaluation of elderly patients (>/=70 years old) enrolled in Phase I clinical trials at University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio-Cancer Therapy Research Center from 2009 to 2011. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2014;5:65-70 doi:10.1016/j.jgo.2013.08.005

24. Yoshioka H, Komuta K, Imamura F, Kudoh S, Seki A, Fukuoka M. Efficacy and safety of erlotinib in elderly patients in the phase IV POLARSTAR surveillance study of Japanese patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung cancer. 2014;86:201-6 doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.09.015

25. Kurishima K, Satoh H, Kaburagi T, Nishimura Y, Shinohara Y, Inagaki M. et al. Erlotinib for elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: Subset analysis from a population-based observational study by the Ibaraki Thoracic Integrative (POSITIVE) Research Group. Molecular and clinical oncology. 2013;1:828-32 doi:10.3892/mco.2013.154

26. Jackman DM, Yeap BY, Lindeman NI, Fidias P, Rabin MS, Temel J. et al. Phase II clinical trial of chemotherapy-naive patients > or = 70 years of age treated with erlotinib for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:760-6 doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5754

27. Chen YM, Tsai CM, Fan WC, Shih JF, Liu SH, Wu CH. et al. Phase II randomized trial of erlotinib or vinorelbine in chemonaive, advanced, non-small cell lung cancer patients aged 70 years or older. Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2012;7:412-8 doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e31823a39e8

28. Wheatley-Price P, Ding K, Seymour L, Clark GM, Shepherd FA. Erlotinib for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in the elderly: an analysis of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study BR.21. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:2350-7 doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2280

29. Platania M, Agustoni F, Formisano B, Vitali M, Ducceschi M, Pietrantonio F. et al. Clinical retrospective analysis of erlotinib in the treatment of elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Targeted oncology. 2011;6:181-6 doi:10.1007/s11523-011-0185-6

30. Morikawa N, Minegishi Y, Inoue A, Maemondo M, Kobayashi K, Sugawara S. et al. First-line gefitinib for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC harboring EGFR mutations. A combined analysis of North-East Japan Study Group studies. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2015;16:465-72 doi:10.1517/14656566.2015.1002396

31. Des Guetz G, Landre T, Westeel V, Milleron B, Vaylet F, Urban T. et al. Similar survival rates with first-line gefitinib, gemcitabine, or docetaxel in a randomized phase II trial in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer and a poor performance status (IFCT-0301). Journal of geriatric oncology. 2015 doi:10.1016/j.jgo.2015.02.002

32. Takahashi K, Saito H, Hasegawa Y, Ando M, Yamamoto M, Kojima E. et al. First-line gefitinib therapy for elderly patients with non-small cell lung cancer harboring EGFR mutation: Central Japan Lung Study Group 0901. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2014;74:721-7 doi:10.1007/s00280-014-2548-z

33. Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Usui K, Maemondo M, Okinaga S, Mikami I. et al. First-line gefitinib for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harboring epidermal growth factor receptor mutations without indication for chemotherapy. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:1394-400 doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7658

34. Maemondo M, Minegishi Y, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Harada M, Okinaga S. et al. First-line gefitinib in patients aged 75 or older with advanced non-small cell lung cancer harboring epidermal growth factor receptor mutations: NEJ 003 study. Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2012;7:1417-22 doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e318260de8b

35. Nakao M, Muramatsu H, Sone K, Aoki S, Akiko H, Kagawa Y. et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors for non-small-cell lung cancer patients aged 80 years or older: A retrospective analysis. Molecular and clinical oncology. 2015;3:403-7 doi:10.3892/mco.2014.453

36. Costa GJ, Fernandes AL, Pereira JR, Curtis JR, Santoro IL. Survival rates and tolerability of platinum-based chemotherapy regimens for elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Lung cancer. 2006;53:171-6 doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.04.006

37. Yellen SB, Cella DF, Leslie WT. Age and clinical decision making in oncology patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1994;86:1766-70

38. Bai H, Liu Q, Shi M, Zhang J. Erlotinib and gefitinib treatments of the lung cancer in an elderly patient result in gastrointestinal bleeding. Pakistan journal of medical sciences. 2013;29:1278-9

39. Yang JC, Wu YL, Schuler M, Sebastian M, Popat S, Yamamoto N. et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin-based chemotherapy for EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma (LUX-Lung 3 and LUX-Lung 6): analysis of overall survival data from two randomised, phase 3 trials. The Lancet Oncology. 2015;16:141-51 doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71173-8

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Paul Zarogoulidis, M.D, Ph. D, Pulmonary Department-Oncology Unit, “G. Papanikolaou” General Hospital, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece. Fax: 00302310992424; Mobile: 00306977271974; E-mail: pzarogcom

Corresponding author: Paul Zarogoulidis, M.D, Ph. D, Pulmonary Department-Oncology Unit, “G. Papanikolaou” General Hospital, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece. Fax: 00302310992424; Mobile: 00306977271974; E-mail: pzarogcom

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact