Impact Factor

ISSN: 1837-9664

J Cancer 2021; 12(15):4443-4454. doi:10.7150/jca.57894 This issue Cite

Research Paper

An Italian National Survey on Ovarian Cancer Treatment at first diagnosis. There's None so Deaf as those who will not Hear

1. Unit of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy.

2. Laboratory of Translational Research, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy.

3. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, AOUI Verona, University of Verona, Verona VR, Italy.

4. Unit of Surgical Gynecol Oncology, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy.

5. Istituto Nazionale Tumori Fondazione Giovanni Pascale, Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico, Napoli, Italy.

Received 2021-1-6; Accepted 2021-4-27; Published 2021-5-27

Abstract

Objective: Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the most lethal gynecological malignancy, crucial prognostic factors are no gross residual disease and centralization of cases. To evaluate the centralization of EOC patients, we report the results of a survey that shows the daily management of EOC patients in Italy.

Methods: A 49-items electronic unblinded survey assessing demographics, practice characteristics, current opinions and approach to managing advanced EOC at first diagnosis was sent both to general gynecologists (GG) and gynecologic oncologists (GO). Differences in frequency distribution of answers between gynecologists with different expertise were evaluated using Fisher exact test. Multivariable analyses were performed applying generalized linear models.

Results: 84/192 (44%) GG and 108/192 (56%) GO from all Italian regions answered to our survey. GOs declared to perform fertility sparing surgery in early EOC more frequently than GG (p=0.002).

GOs can perform a frozen section and have both a gynecopathologist and a dedicated general surgeon. 89% of GOs consider as “optimal debulking” no gross residual disease and 81% achieve this at upfront cytoreduction in more than 40% of patients. Use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy decreases in higher volume centers (p<0.001) while it is lower in the group of GOs than in the GGs group (p<0.001).

Conclusions: EOC patients are still treated by GGs. GOs perform more upfront surgery and achieve optimal debulking in a greater percentage of patients than GGs. In Italy an adequate centralization of cases has not yet been achieved, and this may have detrimental effects on the quality of treatment.

Keywords: epithelial ovarian cancer, centralization, survey, gynecologic oncologists, cytoreduction

Introduction

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the most lethal gynecological malignancy, with 238,700 new cancer cases and 151,900 cancer deaths worldwide recorded in the 2012 [1]. This malignancy represents the eighth cause of death from cancer in women worldwide [1]. In the year 2016, the Italian Association of Cancer Registries reported 5,200 new cancer cases and 3,302 cancer deaths [2]. Despite well-recognized advances in treatment [3-12], overall mortality rate has not substantially improved [13]. Five-year overall survival (OS) is generally low, being around 45% [14] because EOC is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage and no specific symptoms or screening tools are available for early diagnosis [7,14,15]. When EOC is limited to the ovary (stages IA and IB), 5-year OS rises to 92%. However, only 15% of all EOC are found at these early stages [14], therefore the diagnosis of an EOC is often associated with a heavy impact on women's life [16,17].

Although new prognostic factors are continuously researched [7,18-22] and others such as age, obesity, performance status, histology, stage, and grade are well established [18], the most important aspects associated with improved survival are the absence of macroscopic residual disease at the end of primary surgery and centralization of cases [18,23]. Several reports and meta-analysis provide evidence to suggest that EOC patients who receive treatment in high volume and specialized centers have a significantly improved survival compared to those managed elsewhere [13, 23-30]. High volume centers usually guarantee high-quality surgery, maximal cytoreduction and very high rates of no residual disease [23, 26-28]. Usually EOC patients are consistently treated according to established guidelines at high volume centers [31] and when better surgical results are achieved EOC treatment becomes cost-effective [32]. Despite this compelling evidence, many EOC patients are not referred to high-volume, specialized centers [33]. In 2013, an Italian regional audit concerningly reported that most of the hospitals (84%) treating EOC patients were low volume centers (≤ 10 operated patients/year) and managed 22.3% of EOC patients, while only 45.6% of EOC patients were treated in high volume EOC centers (≥ 21 patients/year) [23]. These differences translated into a significantly better survival among patients managed at high-volume centers [23]. Similar findings have been described by a recent report of The Italian National Agency for Regional Healthcare Services (AGENAS) which showed that 316/415 (76%) hospitals treat less than 10 EOC patients per year, while only 50/415 (3.3%) hospitals manage more than 20 EOC patients for year [34].

With the purpose of understanding whether there has been an improvement in the centralization of the cases, we report the results from a survey aimed at drawing a true picture of the daily management of EOC at primary diagnosis in Italy.

Materials and methods

A 49-items electronic unblinded survey (Table 1) assessing demographics, practice characteristics, and current opinions and approach to managing advanced EOC at first diagnosis was sent to the Multicenter Italian Trials in Ovarian Cancer and Gynecologic Malignancies (MITO) Group members, Menopausa-Italia Group members and was published on the website of the Italian Association of the Ostetricians and Gynecologists (AOGOI). The results were collected by using Google Forms available at this link: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1zeXslexB7ODS2x9MQs-hCHC8H8X_nE2HFCPvYhaq-wY/edit. Gynecologists received an email three times with a link to the survey and the free access to the survey link was available on AOGOI web site for three months (https://www.aogoi.it/notiziario/indagine-conoscitiva-sul-trattamento-delle-pazienti-con-prima-diagnosi-di-carcinoma-ovarico/). Participants had to answer to all questions and had the possibility of receiving the result of the questionnaire. The survey was addressed both to general gynecologists and to gynecologists with specific interest in gynecologic oncology. In Italy no subspecialty or formal fellowship in Gynecologic Oncology exists; therefore, we defined the General Gynecologists (GGs) as those gynecologists who are involved in various aspects of Obstetrics and Gynecology during their clinical practice and who occasionally treat malignancies. On the other hand, gynecologists with specific interests in gynecologic oncology (GOs) were defined as those gynecologists who spend the majority of their clinical practice in the treatment of gynecologic malignancies. The first survey request was sent out with an e-mail invitation and link to the survey in April 2019, with a second invitation sent to non-responders three weeks later, and a third and final invitation sent four weeks later. To ensure the validity and reliability of the survey, we followed the recommendations by Tong et all [35]. Demographics of the surveyed cohort were analyzed using R software version 2.15.1. Differences in frequency distribution of survey answers between medical doctors with different expertise were evaluated using Fisher exact test. Multivariable analyses were performed applying generalized linear models. Statistically significant differences were expressed by a P value lower than 0.05.

Results

From 250 surveys sent out 226 replies were included in the final analysis (return rate 90.4%): 34/226 residents (15%) and 192/226 (85%) specialists (Supplementary Table 1) answered. Answers came from different Italian regions and were sorted in three big area such as Northern, Central, and Southern Italy. This study was focused on specialists' point of view and all the following data were based on the answers of these 192 physicians (Table 1).

Among specialists, 84/192 (44%) of the respondents are GGs and 108/192 (56%) are GOs. Half of the GO (54/108) are over 50 years old and 70% of them (76/108) have been working for more than fifteen years. 74% of GOs treat EOC surgically as first operator (FS), while 64% (54/84) of GGs operate as assistant (AS) (Table 2). Gynecologists who work in a center treating 10 EOC patients/year or less are occasionally dedicated to gynecologic oncology in 85% of cases (44/52); on the contrary, in centers treating more than 30 EOC patients/year, gynecologists are dedicated to gynecological oncology as their main activity in 86% of cases (62/72) (Table 2).

Frequency distribution of survey questions and answers of specialists

| Total (N=192) | |

|---|---|

| 1. Where do you work? | |

| a. General Hospital | 126 (66%) |

| b. University Hospital | 36 (19%) |

| c. Research Institute | 30 (16%) |

| d. Private Clinic | 0 (0%) |

| 2. In which area of Italy do you work? | |

| a. Norther Italy | 98 (51%) |

| b. Central Italy | 26 (14%) |

| c. Southern Italy | 68 (35%) |

| 3. You are: | |

| a. Resident | 0 (0%) |

| b. Specialist | 192 (100%) |

| 4. How old are you? | |

| a. < 30 years | 0 (0%) |

| b. 30-35 years | 24 (12%) |

| c. 36-40 years | 28 (15%) |

| d. 41-50 years | 50 (26%) |

| e. > 50 years | 90 (47%) |

| 5. How many years of practice do you have? | |

| a. ≤ 5 years | 28 (15%) |

| b. 6-10 years | 18 (9%) |

| c. 11-15 years | 26 (14%) |

| d. > 15 years | 120 (62%) |

| 6. Do you practice Gynecologic Oncology? | |

| a. Occasionally | 84 (44%) |

| b. It is my principal activity | 108 (56%) |

| 7. Do you perform EOC surgery as: | |

| a. First surgeon | 110 (57%) |

| b. Assistant surgeon | 82 (43%) |

| 8. How long have you been practicing oncological gynecology? | |

| a. ≤ 5 years | 44 (23%) |

| b. 6-10 years | 36 (19%) |

| c. > 10 years | 112 (58%) |

| 9. In your center, how many ovarian cancer patients are treated each year? | |

| a. ≤10 | 52 (27%) |

| b. 11-20 | 48 (25%) |

| c. 21-30 | 20 (10%) |

| d. >30 | 72 (38%) |

| 10. In your center, how many ovarian cancer patients at stage I-II are treated each year? | |

| a. ≤5/year | 66 (34%) |

| b. 6-10/ year | 74 (39%) |

| c. 11-15/year | 26 (14%) |

| d. 15/ year | 26 (14%) |

| 11. In your center, which surgical approach do you use in patients with early ovarian cancer? | |

| a. Laparoscopic/both | 150 (78%) |

| b. Laparotomic | 42 (22%) |

| 12. In your center, in what percentage of cases do you use the laparoscopic approach? | |

| a. ≤10 | 56 (29%) |

| b. 11-30 | 54 (28%) |

| c. > 30% | 82 (43%) |

| 14. In your center, how many ovarian cancer patients are candidated to fertility sparing surgery each year? | |

| a. 0-2/year | 120 (62%) |

| c. 2-5/year | 62 (32%) |

| b. > 5/year | 10 (5%) |

| 18. In your center, which surgical approach do you use in patients with ovarian tumors who are candidates for fertility sparing surgery? | |

| a. Laparoscopic/both | 170 (89%) |

| b. Laparotomic | 22 (11%) |

| 19. In your center, in what percentage of cases do you adopt the laparoscopic approach in patients candidated for fertility sparing surgery?* | |

| a. 0% | 26 (14%) |

| b. < 25% | 60 (33%) |

| c. 25-50% | 22 (12%) |

| d. 50-100% | 50 (27%) |

| e. 100% | 26 (14%) |

| 21. In your center, do you have the opportunity to perform an extemporaneous intraoperative examination? | |

| a. Yes | 186 (97%) |

| b. No | 6 (3%) |

| 22. In your center, do you have a dedicated pathologist available? | |

| a. Yes | 126 (66%) |

| b. No | 66 (34%) |

| 23. Do you have a dedicated general surgeon on your team? | |

| a. Yes | 124 (65%) |

| b. No | 68 (35%) |

| 24. What do you consider as optimal cytoduction? | |

| a. No gross residual disease | 152 (79%) |

| b. Residual disease ≤ 0.5 cm | 20 (10%) |

| c. Residual disease ≤ 1 cm | 20 (10%) |

| 25. In your center, who evaluate the residual disease after the surgery? | |

| a. The first operator | 138 (75%) |

| b. A second surgeon | 2 (1%) |

| c. The patient undergoes a CT scan after the surgery | 44 (24%) |

| 26. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you get optimal cytoreduction? | |

| a. <20% | 34 (18%) |

| b. 21-40% | 34 (18%) |

| c. 41-60% | 50 (26%) |

| d. 61-80% | 40 (21%) |

| e. >80% | 34 (18%) |

| 28. In your center, in cases where you suspect the impossibility of direct cytoreduction, do you always perform a diagnostic laparoscopy before laparotomy? | |

| a. Yes | 154 (80%) |

| b. No | 38 (20%) |

| 29. In your center, in cases where you suspect the impossibility of direct cytoreduction, do you always perform a minilaparotomy before laparotomy? | |

| a. Yes | 28 (15%) |

| b. No | 164 (85%) |

| 31. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a diaphragmatic resection? | |

| a. 0% | 88 (46%) |

| b. 1%-20% | 76 (40%) |

| c. 21-40% | 12 (6%) |

| d. >40% | 16 (8%) |

| 32. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a diaphragmatic peritonectomy? * | |

| a. 0% | 56 (30%) |

| b. <25% | 48 (26%) |

| c. 25-50% | 36 (19%) |

| d. 51-75% | 28 (15%) |

| e. 76-100% | 18 (10%) |

| 34. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a bowel resection? | |

| a. < 5% | 94 (49%) |

| b. 5-10% | 56 (29%) |

| c. 10-20% | 26 (14%) |

| d. >20% | 16 (8%) |

| 35. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a splenectomy? | |

| a. <5% | 126 (66%) |

| b. 5%-15% | 50 (26%) |

| c. > 15% | 16 (8%) |

| 36. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a liver resection? | |

| a. 0% | 64 (33%) |

| b. 1-10% | 118 (61%) |

| c. >10% | 10 (5%) |

| 37. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform multiple liver resection? | |

| a. 0% | 126 (66%) |

| b. 1-10% | 60 (31%) |

| c. >10% | 6 (3%) |

| 38. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a distal resection of the pancreas? | |

| a. 0% | 114 (59%) |

| b. 1-5% | 64 (33%) |

| c. >5% | 14 (7%) |

| 39. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a cholecystectomy? | |

| a. 0% | 56 (29%) |

| b. 1-10% | 118 (61%) |

| c. >10% | 18 (9%) |

| 40. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy? | |

| a. 0% | 52 (27%) |

| b. 1-25% | 50 (26%) |

| c. 26-50% | 42 (22%) |

| d. > 50% | 48 (25%) |

| 41. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a systematic lombo-aortic lymphadenectomy? | |

| a. 0% | 62 (32%) |

| b. 1-25% | 68 (35%) |

| c. 26-50% | 28 (15%) |

| d. >50% | 34 (18%) |

| 42. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform only bulky lymph nodes removal? | |

| a. <25% | 44 (23%) |

| b. 25-50% | 56 (29%) |

| c. 51-75% | 34 (18%) |

| d. 76-100% | 58 (30%) |

| 43. For patients not eligible for surgery, neoadjuvant chemotherapy is decided based on histological exam: | |

| a. Yes, in the majority of cases | 88 (46%) |

| b. Yes, always | 96 (50%) |

| c. Often, citologic examination of ascitic fluid is sufficient | 8 (4%) |

| 44. In your center, what percentage of patients do you refer to neoadjuvant chemotherapy? | |

| a. <20% | 54 (28%) |

| b. 20-30% | 64 (33%) |

| c. 31-40% | 38 (20%) |

| d. >40% | 36 (19%) |

| 45. In your center, what type of neoadjuvant chemotherapy do your patients receive? | |

| a. Carboplatin and placlitaxel | 160 (83%) |

| b. Carboplatin alone | 10 (5%) |

| c. Carboplatin and other drug | 16 (8%) |

| d. Other drug combinations | 6 (3%) |

| 46. In your center, how many cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy do your patients receive on average before surgery? | |

| a. 3 | 122 (64%) |

| b. 4 | 14 (7%) |

| c. ≥5 | 56 (29%) |

| 48. The answers to these questions are based on? | |

| a. Rough estimate | 158 (82%) |

| b. Database | 34 (18%) |

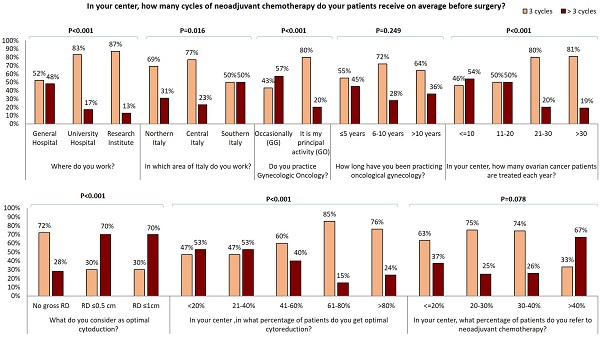

GOs declared to perform fertility sparing surgery in early EOC more frequently than GG (p=0.002) (Figure 1A). In particular, a higher number of fertility-sparing approaches per year was reported by specialists from central Italy and both laparoscopy and fertility sparing were particularly employed in research institutes (Figure 1A-1B).

Influence of gynecological oncological practice on answers to survey questions

| Do you practice Gynecologic Oncology? | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. Occasionally (N=84) | b. It is my principal activity (N=108) | Total (N=192) | P value | |||||

| 4. How old are you? | 0.352 | |||||||

| a. < 30 years | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |||||

| b. 30-35 years | 14 (17%) | 10 (9%) | 24 (12%) | |||||

| c. 36-40 years | 14 (17%) | 14 (13%) | 28 (15%) | |||||

| d. 41-50 years | 20 (24%) | 30 (28%) | 50 (26%) | |||||

| e. > 50 years | 36 (43%) | 54 (50%) | 90 (47%) | |||||

| 5. How many years of practice do you have? | 0.003 | |||||||

| a. ≤ 5 years | 16 (19%) | 12 (11%) | 28 (15%) | |||||

| b. 6-10 years | 14 (17%) | 4 (4%) | 18 (9%) | |||||

| c. 11-15 years | 10 (12%) | 16 (15%) | 26 (14%) | |||||

| d. > 15 years | 44 (52%) | 76 (70%) | 120 (62%) | |||||

| 7. Do you perform EOC surgery as: | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. First surgeon | 30 (36%) | 80 (74%) | 110 (57%) | |||||

| b. Assistant surgeon | 54 (64%) | 28 (26%) | 82 (43%) | |||||

| 8. How long have you been practicing oncological gynecology? | 0.004 | |||||||

| a. ≤ 5 years | 28 (33%) | 16 (15%) | 44 (23%) | |||||

| b. 6-10 years | 12 (14%) | 24 (22%) | 36 (19%) | |||||

| c. > 10 years | 44 (52%) | 68 (63%) | 112 (58%) | |||||

| 9. In your center, how many ovarian cancer patients are treated each year? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. ≤10 | 44 (52%) | 8 (7%) | 52 (27%) | |||||

| b. 11-20 | 22 (26%) | 26 (24%) | 48 (25%) | |||||

| c. 21-30 | 8 (10%) | 12 (11%) | 20 (10%) | |||||

| d. >30 | 10 (12%) | 62 (57%) | 72 (38%) | |||||

| 10. In your center, how many ovarian cancer patients at stage I-II are treated each year? | 0.503 | |||||||

| a. ≤5/year | 32 (38%) | 34 (31%) | 66 (34%) | |||||

| b. 6-10/ year | 32 (38%) | 42 (39%) | 74 (39%) | |||||

| c. 11-15/year | 8 (10%) | 18 (17%) | 26 (14%) | |||||

| d. 15/ year | 12 (14%) | 14 (13%) | 26 (14%) | |||||

| 11. In your center, which surgical approach do you use in patients with early ovarian cancer? | 0.601 | |||||||

| a. Laparoscopic/both | 64 (76%) | 86 (80%) | 150 (78%) | |||||

| b. Laparotomic | 20 (24%) | 22 (20%) | 42 (22%) | |||||

| 12. In your center, in what percentage of cases do you use the laparoscopic approach? | 0.016 | |||||||

| a. ≤10 | 32 (38%) | 24 (22%) | 56 (29%) | |||||

| b. 11-30 | 16 (19%) | 38 (35%) | 54 (28%) | |||||

| c. > 30% | 36 (43%) | 46 (43%) | 82 (43%) | |||||

| 14. In your center, how many ovarian cancer patients are candidated to fertility sparing surgery each year? | 0.002 | |||||||

| a. 0-2/year | 62 (74%) | 58 (54%) | 120 (62%) | |||||

| c. 2-5/year | 16 (19%) | 46 (43%) | 62 (32%) | |||||

| b. > 5/year | 6 (7%) | 4 (4%) | 10 (5%) | |||||

| 18. In your center, which surgical approach do you use in patients with ovarian tumors who are candidates for fertility sparing surgery? | 0.362 | |||||||

| a. Laparoscopic/both | 72 (86%) | 98 (91%) | 170 (89%) | |||||

| b. Laparotomic | 12 (14%) | 10 (9%) | 22 (11%) | |||||

| 19. In your center, in what percentage of cases do you adopt the laparoscopic approach in patients candidated for fertility sparing surgery?* | 0.007 | |||||||

| a. 0% | 18 (22%) | 8 (8%) | 26 (14%) | |||||

| b. < 25% | 22 (27%) | 38 (37%) | 60 (33%) | |||||

| c. 25-50% | 10 (12%) | 12 (12%) | 22 (12%) | |||||

| d. 50-100% | 16 (20%) | 34 (33%) | 50 (27%) | |||||

| e. 100% | 16 (20%) | 10 (10%) | 26 (14%) | |||||

| 21. In your center, do you have the opportunity to perform an extemporaneous intraoperative examination? | 0.006 | |||||||

| a. Yes | 78 (93%) | 108 (100%) | 186 (97%) | |||||

| b. No | 6 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (3%) | |||||

| 22. In your center, do you have a dedicated pathologist available? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. Yes | 40 (48%) | 86 (80%) | 126 (66%) | |||||

| b. No | 44 (52%) | 22 (20%) | 66 (34%) | |||||

| 23. Do you have a dedicated general surgeon on your team? | 0.002 | |||||||

| a. Yes | 44 (52%) | 80 (74%) | 124 (65%) | |||||

| b. No | 40 (48%) | 28 (26%) | 68 (35%) | |||||

| 24. What do you consider as optimal cytoduction? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. No gross residual disease | 56 (67%) | 96 (89%) | 152 (79%) | |||||

| b. Residual disease ≤ 0.5 cm | 12 (14%) | 8 (7%) | 20 (10%) | |||||

| c. Residual disease ≤ 1 cm | 16 (19%) | 4 (4%) | 20 (10%) | |||||

| 25. In your center, who evaluate the residual disease after the surgery? | 0.319 | |||||||

| a. The first operator | 60 (75%) | 78 (75%) | 138 (75%) | |||||

| b. A second surgeon | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | |||||

| c. The patient undergoes a CT scan after the surgery | 18 (22%) | 26 (25%) | 44 (24%) | |||||

| 26. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you get optimal cytoreduction? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. <20% | 26 (31%) | 8 (7%) | 34 (18%) | |||||

| b. 21-40% | 22 (26%) | 12 (11%) | 34 (18%) | |||||

| c. 41-60% | 14 (17%) | 36 (33%) | 50 (26%) | |||||

| d. 61-80% | 14 (17%) | 26 (24%) | 40 (21%) | |||||

| e. >80% | 8 (10%) | 26 (24%) | 34 (18%) | |||||

| 28. In your center, in cases where you suspect the impossibility of direct cytoreduction, do you always perform a diagnostic laparoscopy before laparotomy? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. Yes | 58 (69%) | 96 (89%) | 154 (80%) | |||||

| b. No | 26 (31%) | 12 (11%) | 38 (20%) | |||||

| 29. In your center, in cases where you suspect the impossibility of direct cytoreduction, do you always perform a minilaparotomy before laparotomy? | 1.000 | |||||||

| a. Yes | 12 (14%) | 16 (15%) | 28 (15%) | |||||

| b. No | 72 (86%) | 92 (85%) | 164 (85%) | |||||

| 31. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a diaphragmatic resection? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. 0% | 58 (69%) | 30 (28%) | 88 (46%) | |||||

| b. 1%-20% | 20 (24%) | 56 (52%) | 76 (40%) | |||||

| c. 21-40% | 0 (0%) | 12 (11%) | 12 (6%) | |||||

| d. >40% | 6 (7%) | 10 (9%) | 16 (8%) | |||||

| 32. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a diaphragmatic peritonectomy?* | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. 0% | 44 (55%) | 12 (11%) | 56 (30%) | |||||

| b. <25% | 20 (25%) | 28 (26%) | 48 (26%) | |||||

| c. 25-50% | 6 (8%) | 30 (28%) | 36 (19%) | |||||

| d. 51-75% | 4 (5%) | 24 (23%) | 28 (15%) | |||||

| e. 76-100% | 6 (8%) | 12 (11%) | 18 (10%) | |||||

| 34. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a bowel resection? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. < 5% | 64 (76%) | 30 (28%) | 94 (49%) | |||||

| b. 5-10% | 18 (21%) | 38 (35%) | 56 (29%) | |||||

| c. 10-20% | 2 (2%) | 24 (22%) | 26 (14%) | |||||

| d. >20% | 0 (0%) | 16 (15%) | 16 (8%) | |||||

| 35. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a splenectomy? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. <5% | 70 (83%) | 56 (52%) | 126 (66%) | |||||

| b. 5%-15% | 10 (12%) | 40 (37%) | 50 (26%) | |||||

| c. > 15% | 4 (5%) | 12 (11%) | 16 (8%) | |||||

| 36. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a liver resection? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. 0% | 50 (60%) | 14 (13%) | 64 (33%) | |||||

| b. 1-10% | 32 (38%) | 86 (80%) | 118 (61%) | |||||

| c. >10% | 2 (2%) | 8 (7%) | 10 (5%) | |||||

| 37. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform multiple liver resection? | 0.011 | |||||||

| a. 0% | 64 (76%) | 62 (57%) | 126 (66%) | |||||

| b. 1-10% | 20 (24%) | 40 (37%) | 60 (31%) | |||||

| c. >10% | 0 (0%) | 6 (6%) | 6 (3%) | |||||

| 38. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a distal resection of the pancreas? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. 0% | 64 (76%) | 50 (46%) | 114 (59%) | |||||

| b. 1-5% | 0 (0%) | 14 (13%) | 14 (7%) | |||||

| c. >5% | 20 (24%) | 44 (41%) | 64 (33%) | |||||

| 39. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a cholecystectomy? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. 0% | 38 (45%) | 18 (17%) | 56 (29%) | |||||

| b. 1-10% | 38 (45%) | 80 (74%) | 118 (61%) | |||||

| c. >10% | 8 (10%) | 10 (9%) | 18 (9%) | |||||

| 40. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. 0% | 12 (14%) | 40 (37%) | 52 (27%) | |||||

| b. 1-25% | 20 (24%) | 30 (28%) | 50 (26%) | |||||

| c. 26-50% | 20 (24%) | 22 (20%) | 42 (22%) | |||||

| d. > 50% | 32 (38%) | 16 (15%) | 48 (25%) | |||||

| 41. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform a systematic lombo-aortic lymphadenectomy? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. 0% | 14 (17%) | 48 (44%) | 62 (32%) | |||||

| b. 1-25% | 38 (45%) | 30 (28%) | 68 (35%) | |||||

| c. 26-50% | 14 (17%) | 14 (13%) | 28 (15%) | |||||

| d. >50% | 18 (21%) | 16 (15%) | 34 (18%) | |||||

| 42. In your center, in what percentage of patients do you perform only bulky lymph nodes removal? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. <25% | 32 (38%) | 12 (11%) | 44 (23%) | |||||

| b. 25-50% | 32 (38%) | 24 (22%) | 56 (29%) | |||||

| c. 51-75% | 8 (10%) | 26 (24%) | 34 (18%) | |||||

| d. 76-100% | 12 (14%) | 46 (43%) | 58 (30%) | |||||

| 43. For patients not eligible for surgery, neoadjuvant chemotherapy is decided based on histological exam: | 0.003 | |||||||

| a. Yes, in the majority of cases | 38 (45%) | 50 (46%) | 88 (46%) | |||||

| b. Yes, always | 38 (45%) | 58 (54%) | 96 (50%) | |||||

| c. Often, citologic examination of ascitic fluid is sufficient | 8 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (4%) | |||||

| 44. In your center, what percentage of patients do you refer to neoadjuvant chemotherapy? | 0.078 | |||||||

| a. <20% | 24 (29%) | 30 (28%) | 54 (28%) | |||||

| b. 20-30% | 26 (31%) | 38 (35%) | 64 (33%) | |||||

| c. 31-40% | 12 (14%) | 26 (24%) | 38 (20%) | |||||

| d. >40% | 22 (26%) | 14 (13%) | 36 (19%) | |||||

| 45. In your center, what type of neoadjuvant chemotherapy do your patients receive? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. Carboplatin and placlitaxel | 58 (69%) | 102 (94%) | 160 (83%) | |||||

| b. Carboplatin alone | 8 (10%) | 2 (2%) | 10 (5%) | |||||

| c. Carboplatin and other drug | 14 (17%) | 2 (2%) | 16 (8%) | |||||

| d. Other drug combinations | 4 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 6 (3%) | |||||

| 46. In your center, how many cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy do your patients receive on average before surgery? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. 3 | 36 (43%) | 86 (80%) | 122 (64%) | |||||

| b. 4 | 8 (10%) | 6 (6%) | 14 (7%) | |||||

| c. ≥5 | 40 (48%) | 16 (15%) | 56 (29%) | |||||

| 48. The answers to these questions are based on? | < 0.001 | |||||||

| a. Rough estimate | 82 (98%) | 76 (70%) | 158 (82%) | |||||

| b. Database | 2 (2%) | 32 (30%) | 34 (18%) | |||||

All GOs who participated to our survey work in centers where there is the possibility to perform an intraoperative frozen section and in more than 70% of cases a pathologist with particular expertise in gynecological oncological pathology (gynecolopathologist) and a general surgeon dedicated to EOC treatment are available (80% and 74% respectively); conversely GGs declared the availability of dedicated gynecopathologist and a general surgeon only in 48% and 52% of cases respectively.

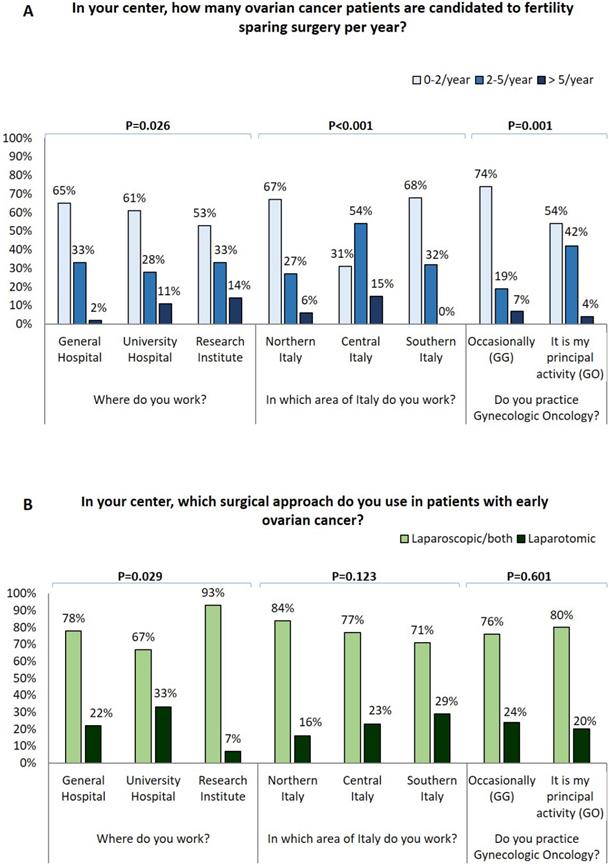

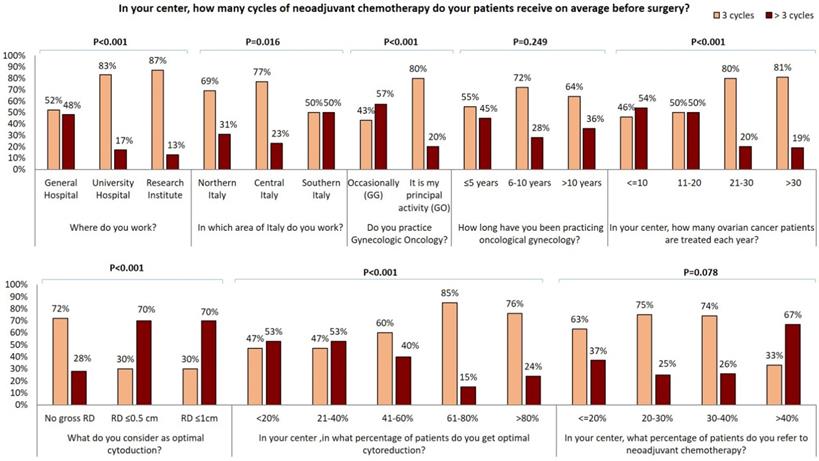

The vast majority of GOs (96/108, 89%) consider as “optimal debulking” no gross residual disease (RD) and 88/108 (81%) achieve this at upfront cytoreduction in more than 40% of patients. Conversely, 67% (56/84) of GGs occasionally dedicated to gynecologic oncology, consider as “optimal debulking” no gross RD whilst 19% (16/84) of them consider as “optimal debulking” RD ≤ 1 cm. Besides, less than half of GGs declared to achieve complete cytoreduction in more than 40% of patients. Particularly, “optimal debulking” is considered as no gross RD by 93% of responders working at Research centers, 83% of responders working at University centers and only 75% of responders working at general hospitals. Interestingly, the percentage of this answer raises with the increase of the years of experience in gynecological oncology and the number of EOC patients treated each year in the center (Figure 2A) Moreover, the RD is evaluated by the first operator in 75% of cases; 24% of the responding specialists utilize a postoperative CT scan to evaluate the completeness of cytoreduction; 1% of responders declared that completeness of cytoreduction was evaluated by a second surgeon (Table 1). Those declaring that gross RD is defined by the first operator consider no gross RD as optimal debulking in a larger percentage of cases (Figure 2).

A) Influence of surgical centre, geographical area, oncological practice on number of ovarian cancer patients candidate to fertility sparing surgery for year; B) Influence of surgical centre, geographical area, oncological practice on surgical approach used in early stage ovarian cancer patients.

Influence of surgical centre, years of experience in oncological gynecology, number of ovarian cancer patients treated for year and modality of residual tumor evaluation on optimal cytoreduction definition.

GGs who answered to our survey performed less upper abdominal surgery than GOs (Table 2). 69% of GGs who answered to the survey never perform a diaphragmatic resection while 52% of GOs perform a diaphragmatic resection in 1-20% of EOC and 20% declare to perform it in a higher percentage of patients. Similarly, 52% of GGs never perform a diaphragmatic peritonectomy in comparison with only the 11% of GOs.

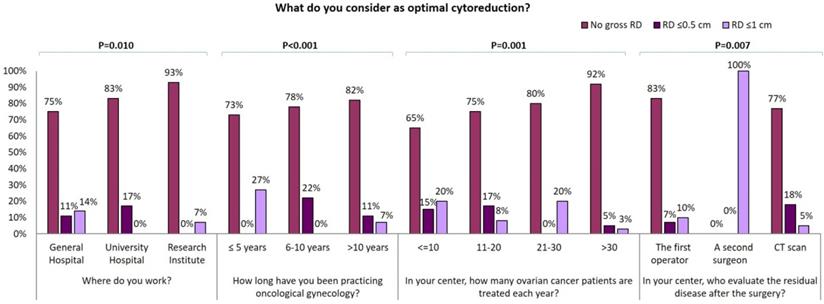

In our survey 72% of GOs and only 24% of GGs perform bowel resection in more than 5% of EOC cases. Moreover, 60% of GGs never perform hepatic surgery and 38% perform it in less than 10% of EOC. Conversely, 80% of GOs declare to carry out hepatic surgery in 1-10% of patients and 7% perform it in more than 10% of patients. Similar data were collected about other surgical practices: 76% of GGs versus 46% of GOs never perform a distal resection of the pancreas while cholecystectomy is never carried out by 45% of GGs versus 17% of GOs. Systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy are never carried out by 37% and 44% of GOs respectively, versus 14% and 17% of GG. In fact, 43% of GOs and only 14% of GGs perform the resection only of gross lymph nodes in 75-100% of patients. 72% of the responders administer neoadjuvant chemotherapy (CHT) to more than 20% of patients: 83% of responders administer carboplatin and paclitaxel while carboplatin-only therapy is delivered only by 10 responders in Northern Italy (Table 1). 64% (122/192) of responders administer three cycles of neoadjuvant CHT while >3 cycles are administered by majority larger percentage of specialists from southern Italy (Figure 3). Of note, gynecologists who achieve optimal cytoreduction in at least 40% of patients declare to adopt an approach of neoadjuvant CHT in a lower percentage of cases and to administer 3 cycle of therapy in the majority of cases. Conversely, 70% of those gynecologists who consider optimal RD ≤1 cm declare to administer more than 3 cycles of chemotherapy (Figure 3). Moreover, specialists who treat more than 40% of EOC patients with neoadjuvant chemotherapy administer more than 3 cycles of neoadjuvant CHT in 67% of cases. 48% of physicians working in general hospital administer more than 3 cycles of CHT in comparison with 17% and 13% of those working in university hospitals and research institutes respectively (p<0.001). Besides, the percentage of gynecologists who administer more than 3 cycles of CHT in the neoadjuvant setting decrease in centers where a larger number of EOC are registered each year (p<0.001) and is lower in the group of GOs than in the GGs group (20% vs 57%, p<0.001). Moreover, the percentage of gynecologists who administer more than 3 cycles of neoadjuvant CHT shows a decreasing trend among physicians with a longer experience in gynecologic oncology and correlation between experience in gynecologic oncology and number of neoadjuvant CHT cycles became statistically significant (p=0.017) comparing specialist who administer ≤ 4 cycles with specialist administering > 4 cycles. 110/192 (57.3%) specialists declared to operate as first surgeon (FS) and 82/192 (42.7%) as assistant (AS) (Supplementary Table 2). ASs are significantly younger and less experienced that FSs, 34% of ASs versus 73% of FSs declared to practice gynecologic oncology as principal activity. 37% of ASs versus 20 % of FSs (P=0.045) work in center where no more than 10 cases of EOC are treated each year. ASs more frequently work in centers were only 0-2 patients per year are candidate to fertility sparing (73% of ASs vs 55% of FSs, P=0.002) and were laparoscopy is never adopted in patients candidate to laparoscopy (24% of ASs vs 7% of FSs, P=0.010). 51% of ASs versus 75% of FSs has a dedicated general surgeon in his team. 48% of ASs declared to obtain an optimal cytoreduction in less than 40% of patients while only 28% of FSs has the same opinion (P=0.002). ASs in comparison to FSs declared to work in center where less aggressive surgery is performed: they never perform diaphragmatic resection (61% vs 35%), diaphragmatic peritonectomy (42% vs 22%), liver resection (51% vs 20%), distal resection of the pancreas (71% vs 51%) and cholecystectomy (37% vs 24%) and where less than 5% of EOC patients receive bowel resection (71% vs 33%) and splenectomy (80% vs 55%). On the contrary, 37% of ASs versus 16% of FSs (P=0.018) and 27% versus 11% (P=0.016) declared to perform respectively systematic pelvic and lombo-aortic lymphadenectomy in more than 50% of patients. Similarly, 37% of ASs declared to only perform bulky lymph nodes removal in less than 25% of cases versus only 13% of FSs. Furthermore, only 12% of ASs versus 24% of FS (P=0.011) work in centers where more than 40% of patients receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy but 46% of ASs and only 27% of FSs declare that patients treated with chemotherapy receive more than 3 cycles of treatment.

Influence of surgical centre, geographical area, oncological practice, years of experience in oncological gynecology, number of ovarian cancer patients treated for year, optimal residual tumor definition, percentage of optimally cytoreducted patients and percentage of patients submitted to neoadjuvant chemotherapy on number of neoadjuvant chemotherapy cycles.

Discussion

The present survey was created to assess how EOC patients are treated in Italy in the everyday clinical practice and to understand which geographic, professional or clinical variables influence the physicians' therapeutic choices. Among the other findings, the present national analysis shows that in 2020 there is a wide variation of treatment policies for EOC patients between dedicated gynecologic oncologists and general gynecologists and that still a vast proportion of gynecologists in Italy treat ovarian cancer in low-volume hospitals.

We focused our data analysis on the perspective of the 192 responding specialists and we based the principal comparisons on the differences between GGs and GOs.

Initially, we observed that the percentage of physicians mainly dedicated to gynecologic oncology is higher in centers were a higher number of EOC are treated each year. This data could suggest some considerations: the first is that centers with small numbers of EOC patients do not usually treat gynecological cancers, while probably gynecologists who work in higher-volume centers are also likely to treat more patients with gynecological cancers other than the ovary.

Considering only specialist ASs, most are younger, less experienced, work in low volume center and are occasionally dedicated to gynecologic oncology so most of their answers resemble with those of GGs. Notably, we observed that GOs perform fertility-sparing surgery in a significantly larger percentage of early EOC than GGs. Of note, both fertility-sparing surgery and laparoscopic approach are used more commonly at research centers. This is in line with international guidelines which suggest the performance of laparoscopy and fertility sparing procedures only at referral centers [36]. It is essential to note that in younger patients with early EOC, expert GOs can perform a less invasive approach but also a less aggressive surgery ensuring a complete staging and preserving fertility.

EOC treatment requires an interdisciplinary approach and multidisciplinary team that should include GOs, experienced and dedicated general surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, psychologists, nutritionists and researchers [33,37]. In our survey, the majority of GOs work in centers where there is always the possibility to perform an intraoperative frozen section and where a gynecopathologist and a general surgeon dedicated to EOC treatment are generally available; on the other hand, only a small proportion of GGs declare to have the possibility of such a multidisciplinary collaboration.

Several studies have shown that cytoreduction < 1 cm RD provides relevant survival benefits and that no gross RD at the end of initial surgery is associated with significantly longer overall survival, compared to suboptimal cytoreduction [38,39]. In our survey, almost all GOs consider as “optimal debulking” no gross RD while only 67% of GGs is of the same opinion and declare to achieve complete cytoreduction at up front surgery. Interestingly, the percentage of specialists that consider no gross RD as “optimal debulking” is higher among those who work in research centers, have a longer expertise or manage a higher number of EOC per year. On the other hand, most specialists who consider as optimal a RD ≤1 cm work in general hospitals, regardless of age, experience and time spent for gynecological oncology.

It has been clearly demonstrated that the rate of optimal cytoreduction can be sensibly improved by inclusion of upper abdominal procedures [40]. Consequently, cancer centers routinely offer splenectomy, diaphragm resection, celiac nodal resection, and/or multiple bowel resections, cholecystectomy, partial pancreatectomy [41-45]. Notably, GGs who answered to our survey perform less upper abdominal surgery than GOs: about 70% of GGs versus 30% of GOs never perform diaphragmatic resection and similarly about half of GGs never perform a diaphragmatic peritonectomy in comparison with only a small percentage of GOs. Liver metastases account for 18% of parenchymal disease and have been described as the second most common cause of stage IV EOC in a large GOG study [41,47]. Complete resection rates vary from 56 to 87.5% among studies reported in the literature [48]. Complete liver metastases resection seems to depend on metastatization pattern; it has been proposed that metastases due to hematogenous spread should be submitted to neo-adjuvant chemotherapy whilst metastases due to transcoelomic seeding could be successful resected [48]. Interestingly, in our survey, 60% of GGs and only 13% of GOs declared that they never perform hepatic surgery. Bowel resection is one of the most common procedures performed to achieve optimal RD and is estimated that it is required in approximately 50% of optimal cytoreductive operations [49]. 76% of the responding GGs carry out bowel resection in < 5% of EOC while the vast majority of GOs perform it in a high percentage of cases. Moreover, the greatest number of procedures on the upper abdomen are reported by physicians working in centers of central and northern Italy. Lymphatic spread is a common finding and an important prognostic factor in both early and advanced EOC [50]. Recently, the LION trial indicated that systematic lymphadenectomy does not offer a survival benefit in advanced EOC patients with no gross lymph node metastases, and that paraaortic and pelvic lymphadenectomy is still warranted in macroscopically suspicious nodes to achieve complete cytoreduction [50]. Within our cohort of specialists, about 40% of GOs and 15% of GGs never perform systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy; similar percentages of responders perform only resection of gross lymph nodes in 75-100% of patients. Multivisceral resections should be performed only if a complete cytoreduction with absent RD can be achieved [37]. In our survey, RD is judged in a large majority of cases by the first operator and only a small number of specialists evaluate it using postoperative CT scan. Diagnostic laparoscopy was suggested as a feasible approach to assess intraperitoneal diffusion of EOC and the likelihood of complete cytoreduction [51]. In our cohort, no significant differences in the use of laparoscopic approach was observed between GOs and GGs. Despite upfront debulking surgery remains the best treatment of advanced EOC, since the publication of the EORTC 55971 trial [52] and CHORUS trial [53] many centers promote the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy associating it to a reduction in surgical morbidity. A concern about a policy of systematic adoption of diagnostic laparoscopy as a triage for patients with advanced EOC is that it may be used by less experienced gynecologists; the consequence of this policy may be to send too many patients to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, in order to perform a potentially less demanding interval debulking surgery. Most of the gynecologists who answered our survey adopt neoadjuvant therapy in more than 20% of EOC cases and administer a combined carboplatin-paclitaxel chemotherapy, while only a small number of responders, from northern Italy, use carboplatin-only chemotherapy. Generally, approximately 40% of EOC patients present with malnutrition, bowel dysfunction, extensive upper abdominal or extraperitoneal disease, large-volume ascites, advanced age and associated comorbidities. Many of these EOC patients will receive neoadjuvant CHT with consideration of interval cytoreductive surgery [54]. The majority of the responding specialists established the appropriate number of neoadjuvant CHT cycles as three, but this number is often higher for physicians who candidate more patients to neoadjuvant therapy. The percentage of physicians that administer more than 3 cycles of neoadjuvant CHT varies between the different clinical centers and between different areas of Italy as well as is higher among specialists who occasionally practice gynecological oncology or those who work in centers where a small number of EOC is treated. On the other hand, the percentage of gynecologists administering more than 3 neoadjuvant CHT cycles is lower between those who consider no gross RD as optimal debulking and who declare to obtain complete cytoreduction in a larger percentage of patients.

This survey highlights how the figure of the GO, particularly FSs, and of the other specialists dedicated to the treatment of ovarian cancer is fundamental to guarantee the best treatment for EOC patients. Compliance with the quality indicators such as percentage of up-front surgery, of optimal RD achieved, of patients submitted to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, number of cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, use of minimally invasive surgery can only be obtained by managing high volumes of EOC patients and with continuous training. Although many studies and guidelines have highlighted the need to centralize the treatment of ovarian cancer in high volume centers, it seems that this recommendation is not yet respected in a vast proportion of cases.

Even the blindly obvious is never too obvious for everyone. Knowing the real world is essential to start promoting changes in the treatment of EOC patients. Despite the fact that since 2004 the Italian national guidelines program has supported centralization for EOC patients [55], several authors over time have highlighted a lack of centralization [56] which still seems to persist (Table 1) and that likely reflects into a suboptimal treatment of affected patients. The national health system, the scientific societies and first of all the individual specialists (gynecologists, oncologists, general surgeons, general practitioners) should guarantee all patients the most appropriate treatments by directing them to the centers with greater competence. In the absence of a structured cancer network, the individual specialist should voluntarily centralize the patient to the nearest competent center avoiding inadequate treatments and wasted time that could have a detrimental impact on survival.

Abbreviations

EOC: epithelial ovarian cancer; OS: overall survival; AGENAS: The Italian National Agency for Regional Healthcare Services; MITO: Multicenter Italian Trials in Ovarian Cancer and Gynecologic Malignancies; AOGOI: Italian Association of the Ostetricians and Gynecologists; GGs: General Gynecologists; GOs: gynecologists with specific interests in gynecologic oncology; AS: assistant; RD: residual disease; CHT: chemotherapy; FS: first surgeon.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary tables.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all Colleagues who have helped to spread the survey, in particular, Dr Sandro Pignata and the “Multicenter Italian Trials in Ovarian Cancer and Gynecologic Malignancies Group”, Dr Elsa Viora and the “Italian Association of the Ostetricians and Gynecologists” and the Colleagues of “Menopausa-Italia Group”. We want to thank Drs Corrado Debbi and Ezio Bergamini for their kind assistance. We are really grateful to all Colleagues who responded to our survey.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. A Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87-108

2. Reggio Emilia, Italy. Mangone L, Pinto C, I numeri del cancro in Italia, 2016. http://www.registri-tumori.it/PDF/AIOM2016/I numeri_del_cancro _2016.

3. Lheureux S, Braunstein M, Oza AM. Epithelial ovarian cancer: Evolution of management in the era of precision medicine. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:280-304

4. Harries M, Gore M. Part I: chemotherapy for epithelial ovarian cancer-treatment at first diagnosis. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:529-36

5. Covens A, Carey M, Bryson P, Verma S, Fung Kee Fung M, Johnston M. Systematic review of first-line chemotherapy for newly diagnosed postoperative patients with stage II, III, or IV epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;85:71-80

6. de la Motte Rouge T, Ray-Coquard I, You B. Traitements médicaux des cancers de l'ovaire lors de la prise en charge initiale. Article rédigé sur la base de la recommandation nationale de bonnes pratiques cliniques en cancérologie intitulée « Conduites à tenir initiales devant des patientes atteintes d'un cancer épithélial de l'ovaire » élaborée par FRANCOGYN, CNGOF, SFOG, GINECO-ARCAGY sous l'égide du CNGOF et labellisée par l'INCa [Medical treatment in ovarian cancers newly diagnosed: Article drafted from the French Guidelines in oncology entitled "Initial management of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer" developed by FRANCOGYN, CNGOF, SFOG, GINECO-ARCAGY under the aegis of CNGOF and endorsed by INCa]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol. 2019;47:222-237

7. Posadas EM, Davidson B, Kohn EC. Proteomics and ovarian cancer: implications for diagnosis and treatment: a critical review of the recent literature. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16:478-84

8. Perez-Fidalgo JA, Grau F, Fariñas L, Oaknin A. Systemic treatment of newly diagnosed advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: From chemotherapy to precision medicine. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;158:103209

9. Lorusso D, Ceni V, Daniele G, Salutari V, Pietragalla A, Muratore M. et al. Newly diagnosed ovarian cancer: Which first-line treatment? Cancer Treat Rev. 2020;91:102111

10. González Martín A, Bratos R, Márquez R, Alonso S, Chiva L. Bevacizumab as front-line treatment for newly diagnosed epithelial cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2013;13:123-9

11. Swart AM, Burdett S, Ledermann J, Mook P, Parmar MK. Why i.p. therapy cannot yet be considered as a standard of care for the first-line treatment of ovarian cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:688-95

12. Trainer AH, Meiser B, Watts K, Mitchell G, Tucker K, Friedlander M. Moving toward personalized medicine: treatment-focused genetic testing of women newly diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:704-16

13. Reade CJ, Elit LM. Current Quality of Gynecologic Cancer Care in North America, Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2019;46:1-17.

14. American Joint Committee on Cancer. Ovary and Primary Peritoneal Carcinoma. In: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer. 2010:419-428

15. Das PM, Bast RC Jr. Early detection of ovarian cancer, Biomark Med. 2008;2:291-303.

16. Mangone L, Mandato VD, Gandolfi R, Tromellini C, Abrate M. The impact of epithelial ovarian cancer diagnosis on women's life: a qualitative study, Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2014;35: 32-8.

17. Pergialiotis V, Pitsouni E, Prodromidou A, Frountzas M, Perrea DN, Vlachos GD. Hormone therapy for ovarian cancer survivors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause. 2016;23:335-42

18. Ezzati M, Abdullah A, Shariftabrizi A, Hou J, Kopf M, Stedman JK. et al. Recent Advancements in Prognostic Factors of Epithelial Ovarian Carcinoma, Int Sch Res Notices. 2014 29;2014:953509.

19. Mandato VD, Magnani E, Abrate M, Casali B, Nicoli D, Farnetti E. et al. Haptoglobin phenotype and epithelial ovarian cancer. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4353-8

20. Mandato VD, Torricelli F, Mastrofilippo V, Ciarlini G, Pirillo D, Annunziata G. et al. AB0 Blood Group and Ovarian Cancer Survival. J Cancer. 2019;10:1949-1957

21. de Graeff P, Crijns AP, de Jong S, Boezen M, Post WJ, de Vries EG. et al. Modest effect of p53, EGFR and HER-2/neu on prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:149-59

22. Assis J, Pereira C, Nogueira A, Pereira D, Carreira R, Medeiros R. Genetic variants as ovarian cancer first-line treatment hallmarks: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;61:35-52

23. Mandato VD, Abrate M, De Iaco P, Pirillo D, Ciarlini G, Leoni M. et al. Clinical governance network for clinical audit to improve quality in epithelial ovarian cancer management. J Ovarian Res. 2013;6:19

24. Woo YL, Kyrgiou M, Bryant A, Everett T, Dickinson HO. Centralisation of services for gynaecological cancers - a Cochrane systematic review. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126:286-90

25. Seagle BL, Strohl AE, Dandapani M, Nieves-Neira W, Shahabi S. Survival Disparities by Hospital Volume Among American Women With Gynecologic Cancers. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2017;1:1-15

26. Huguet M, Perrier L, Bally O, Benayoun D, De Saint Hilaire P, Beal Ardisson D. et al. Being treated in higher volume hospitals leads to longer progression-free survival for epithelial ovarian carcinoma patients in the Rhone-Alpes region of France. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:3

27. Kumpulainen S, Sankila R, Leminen A, Kuoppala T, Komulainen M, Puistola U. et al. The effect of hospital operative volume, residual tumor and first-line chemotherapy on survival of ovarian cancer - a prospective nation-wide study in Finland. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;115:199-203

28. Greggi S, Falcone F, Carputo R, Raspagliesi F, Scaffa C, Laurelli G. et al. Primary surgical cytoreduction in advanced ovarian cancer: An outcome analysis within the MITO (Multicentre Italian Trials in Ovarian Cancer and Gynecologic Malignancies) Group. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140:425-9

29. Kumpulainen S, Grénman S, Kyyrönen P, Pukkala E, Sankila R. Evidence of benefit from centralised treatment of ovarian cancer: a nationwide population-based survival analysis in Finland. Int J Cancer. 2002;102:541-4

30. Geomini PM, Kruitwagen RF, Bremer GL, Massuger L, Mol BW. Should we centralise care for the patient suspected of having ovarian malignancy? Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:95-9

31. Jessmon P, Boulanger T, Zhou W, Patwardhan P. Epidemiology and treatment patterns of epithelial ovarian cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2017;17:427-437

32. Greving JP, Vernooij F, Heintz AP, van der Graaf Y, Buskens E. Is centralization of ovarian cancer care warranted? A cost-effectiveness analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:68-74

33. Aletti GD, Peiretti M. Quality control in ovarian cancer surgery, Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2017; 41: 96-107.

34. https://www.agenas.gov.it/images/agenas/pne/PNE2018_4_giugno.pdf accessed 25 August 2019

35. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups, Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349-57.

36. Ledermann JA, Raja FA, Fotopoulou C, Gonzalez-Martin A, Colombo N, Sessa C; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:iv259

37. Rausei S, Uccella S, D'Alessandro V, Gisone B, Frattini F, Lianos G. et al. Aggressive surgery for advanced ovarian cancer performed by a multidisciplinary team: A retrospective analysis on a large series of patients. Surg Open Sci. 2019;1:43-47

38. Chi DS, Eisenhauer EL, Lang J, Huh J, Haddad L, Abu-Rustum NR. et al. What is the optimal goal of primary cytoreductive surgery for bulky stage IIIC epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC)? Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:559-64

39. Chang SJ, Bristow RE. Evolution of surgical treatment paradigms for advanced-stage ovarian cancer: redefining 'optimal' residual disease, Gynecol Oncol. 2012; 125:483-492.

40. Eisenhauer EL, Abu-Rustum NR, Sonoda Y, Levine DA, Poynor EA, Aghajanian C. et al. The addition of extensive upper abdominal surgery to achieve optimal cytoreduction improves survival in patients with stages IIIC-IV epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:1083-90

41. Gasparri ML, Grandi G, Bolla D, Gloor B, Imboden S, Panici PB. et al. Hepatic resection during cytoreductive surgery for primary or recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142:1509-20

42. Aletti GD, Podratz KC, Jones MB, Cliby WA. Role of rectosigmoidectomy and stripping of pelvic peritoneum in outcomes of patients with advanced ovarian cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:521-6

43. Magtibay PM, Adams PB, Silverman MB, Cha SS, Podratz KC. Splenectomy as part of cytoreductive surgery in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:369-74

44. Eisenkop SM, Spirtos NM, Lin WC. Splenectomy in the context of primary cytoreductive operations for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:344-8

45. Chi DS, Eisenhauer EL, Zivanovic O, Sonoda Y, Abu-Rustum NR, Levine DA. et al. Improved progression-free and overall survival in advanced ovarian cancer as a result of a change in surgical paradigm. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114:26-31

46. Tsolakidis D, Amant F, Van Gorp T, Leunen K, Neven P, Vergote I. Diaphragmatic surgery during primary debulking in 89 patients with stage IIIB-IV epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:489-96

47. Winter WE 3rd, Maxwell GL, Tian C, Sundborg MJ, Rose GS, Rose PG. et al. Gynecologic Oncology Group. Tumor residual after surgical cytoreduction in prediction of clinical outcome in stage IV epithelial ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:83-9

48. Lim MC, Kang S, Lee KS, Han SS, Park SJ, Seo SS. et al. The clinical significance of hepatic parenchymal metastasis in patients with primary epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:28-34

49. Salani R, Zahurak ML, Santillan A, Giuntoli RL 2nd, Bristow RE. Survival impact of multiple bowel resections in patients undergoing primary cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian cancer: a case-control study. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107:495-9

50. Harter P, Sehouli J, Lorusso D, Reuss A, Vergote I, Marth C. et al. A Randomized Trial of Lymphadenectomy in Patients with Advanced Ovarian Neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:822-832

51. Fagotti A, Vizzielli G, De Iaco P, Surico D, Buda A, Mandato VD. et al. A multicentric trial (Olympia-MITO 13) on the accuracy of laparoscopy to assess peritoneal spread in ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:462.e1-462.e11

52. Vergote I, Tropé CG, Amant F, Kristensen GB, Ehlen T, Johnson N. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:943-53

53. Kehoe S, Hook J, Nankivell M, Jayson GC, Kitchener H, Lopes T. et al. Primary chemotherapy versus primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): an open-label, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2015;386:249-57

54. Gourley C, Bookman MA. Evolving Concepts in the Management of Newly Diagnosed Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:2386-2397

55. http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2097_allegato.pdf

56. Sobrero S, Pagano E, Piovano E, Bono L, Ceccarelli M, Ferrero A. et al. Is Ovarian Cancer Being Managed According to Clinical Guidelines? Evidence from a Population-Based Clinical Audit. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26:1615-1623

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Vincenzo Dario Mandato, Unit of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy, Viale Risorgimento n 80, Italy. Phone: +393494640813 - fax: +390522296015; E-mail: dariomandatocom.

Corresponding author: Vincenzo Dario Mandato, Unit of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy, Viale Risorgimento n 80, Italy. Phone: +393494640813 - fax: +390522296015; E-mail: dariomandatocom.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact