Impact Factor

ISSN: 1837-9664

J Cancer 2021; 12(17):5260-5267. doi:10.7150/jca.58726 This issue Cite

Research Paper

External Validation of Six Liver Functional Reserve Models to predict Posthepatectomy Liver Failure after Major Resection for Hepatocellular Carcinoma

1. Hepato-pancreato-biliary center, Zhongda Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing, China.

2. Department of Surgical Oncology, Qin Huai Medical District of Eastern Theater General Hospital, Nanjing, China.

3. Department of Minimally Invasive Surgery, the Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China.

4. Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an, China.

Received 2021-1-27; Accepted 2021-6-13; Published 2021-6-26

Abstract

Objective: To validate and compare the predictive ability of albumin-bilirubin model (ALBI) with other 5 liver functional reserve models (APRI, FIB4, MELD, PALBI, King's score) for posthepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who underwent major hepatectomy.

Methods: Data of patients undergoing major hepatectomy for HCC from 4 hospitals between January 01, 2008 and December 31, 2019 were retrospectively analyzed. PHLF was evaluated according to the definition of the 50-50 criteria. Performances of six liver functional reserve models were determined by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), calibration plot and decision curve analysis.

Results: A total of 745 patients with 103 (13.8%) experienced PHLF were finally included in this study. Among six liver functional reserve models, ALBI showed the highest AUC (0.64, 95% CI: 0.58-0.69) for PHLF. All models showed good calibration and greater net benefit than treating all patients at a limit range of threshold probabilities, but the ALBI demonstrated net benefit across the largest range of threshold probabilities. Subgroup analysis also showed ALBI had good predictive performance in cirrhotic (AUC=0.63) or non-cirrhotic (AUC=0.62) patients.

Conclusion: Among the six models, the ALBI model shows more accurate predictive ability for PHLF in HCC patients undergoing major hepatectomy, regardless of having cirrhosis or not.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, major hepatectomy, preoperative prediction, posthepatectomy liver failure

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common malignancy in the world. Partial hepatectomy (PH) is still the mainstay of curative-intent treatment for HCC [1]. With improvements in surgical techniques and perioperative management, increasing number of HCC patients are able to undergo PH. However, postoperative morbidity and mortality still exists, and posthepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) remains the most common cause of mortality particularly in patients who underwent major hepatectomy [2]. The reported incidence of PHLF is 0.7%-9.1%, especially in patients underwent major hepatectomy as high as 58.22%, and PHLF is shown as the major cause (between 18% and 75%) of postoperative mortality [3-4]. In consideration of such a high incidence, accurate prediction of PHLF is very important for patient selection and perioperative management in HCC patients following major hepatectomy.

Previously, some liver functional reserve models have been created to assess liver function and predict posthepatectomy outcomes in patients with HCC. MELD model was used to predict survival after hepatectomy of HCC patients [5-7], APRI, FIB4 and King's score models were created to assess liver fibrosis and cirrhosis of HBV and HCV patients [8-12]. These models were gradually adopted to predict PHLF and exhibited a certain predictive ability [13-16]. Recently, ALBI and PALBI model were developed to evaluate liver function and used to predict PHLF after hepatectomy for HCC [17-23]. Although various studies demonstrated the usefulness of these liver functional reserve models in prediction of PHLF, few studies compared their accuracy in HCC patients undergoing major hepatectomy.

The aim of this study is to validate and compare the predictive ability of the ALBI model with other 5 existing liver functional reserve models (PALBI, APRI, MELD, FIB4, and King's score) for PHLF in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after major hepatectomy.

Patients and methods

Study design

A multicentric retrospective analysis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent major hepatectomy (≥ 3 segments) from the Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital in Shanghai, Zhongda Hospital, Southeast university in Nanjing, Qin Huai Medical District of Eastern Theater General Hospital in Nanjing and The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiao Tong University in Xi'an between January 01, 2008 and December 31, 2019 were recorded. Inclusion criteria are obeyed strictly as follows: (1) pathologically confirmed as hepatocellular carcinoma; (2) underwent major hepatectomy, major hepatectomy is defined as resection of Couinaud's segmentation 3 and above [4]; (3) no anti-tumor treatment before surgery, such as ablation, TACE; (4) no major blood vessel invasion, bile duct cancer thrombus and distant metastasis; (5) age ≥18. Exclusion criteria: (1) intraoperative radiofrequency ablation, particle placement and other treatments; (2) data were missing on the fifth day after surgery, and PHLF could not be defined.

Surgical technique

The technique of hepatectomy has been previously described [24]. Parenchymal transection was usually achieved under intermittent pedicle clamping (15-minute occlusion and 5-minute reperfusion). Under anesthesia, the hemodynamic management aimed to maintain low central venous pressure to minimize blood loss with reduced volume perfusion.

Variables of interest

Data were collected by direct extraction from electronic health records, complemented by manual curation. Variables of interest in the dataset included: demographics (age, gender, BMI), laboratory measurements (TBIL, ALB, PLT, PT, INR, ALT, AST and Cr), underlying liver disease (HBsAg, HBeAg, HBV-DNA, anti-HCV and antiviral therapy), radiology reports (ascites and cirrhosis), surgical factors (clamping time, blood loss and intraoperative transfusion) and pathological reports (tumor size, tumor number, microvascular invasion and tumor differentiation).

Liver functional reserve models

A total of 6 liver functional reserve models were investigated: ALBI, PALBI, MELD, APRI, FIB4, King's score which were depicted in detail in Table S1. Comparison of these models was performed through discrimination.

Outcomes and definitions

The main outcome of this study was PHLF. The “50-50 criteria” was used as the definition of PHLF in this study: prothrombin activity < 50% and posthepatectomy serum bilirubin > 50 μmol/L, fifth day after operation [25]. To provide a better overview of the predictive abilities on distinct patient populations, this study performed subgroup analyses based on liver cirrhosis according to imaging findings.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as median with the interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. The X2 test or Fisher's exact test was used to analyze categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney ranked sum test for continuous variables. The discrimination ability of models was evaluated by the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC) and area under the curve (AUC). Comparisons between the ROC curves were performed using the corresponding DeLong's tests. We assessed calibration by visualizing calibration of predicted vs. observed risk using loess-smoothed plots. Decision curve analyses were done using the rmda package in R [26]. A two-tailed P values <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata/SE 15.1 (College Station, TX77845, USA) and R (Version 4.0.2, https://www.r-project.org).

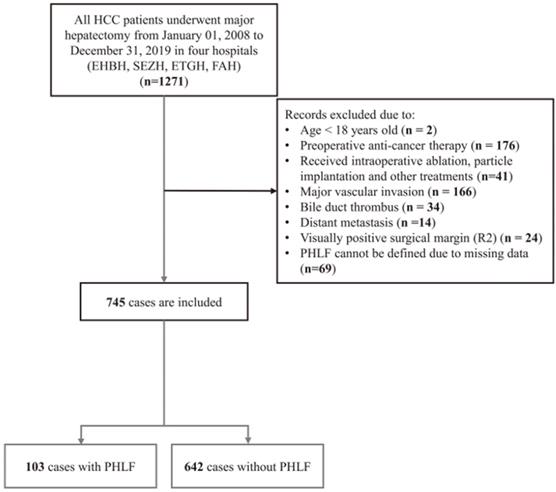

Flow chart of the study.

Results

Baseline characteristics of study population

As was shown in Figure 1, a total of 745 HCC patients were enrolled in the present study, comprising 624 (83.8%) men, with a median age of 53 years (IQR, 45-60 years). Among them, 103 patients experienced PHLF, accounting for 13.8%. The median value of ALBI, PALBI, APRI, MELD, FIB4 and King's score is -2.8 (-3.00 to -2.56), -2.56 (-2.73 to -2.37), 0.52 (0.30-0.88), 7 (6-7), 1.79 (1.06-2.83), and 11.0 (6.06-18.5), respectively. According to the ALBI grade, the majority of patients had grade 1 (532/745, 71.4%), 28.5% (212/745) as grade 2 and 0.1% (1/745) as grade 3. The patient's basic characteristics, preoperative clinical indicators and six model information are shown in Table 1. There was statistical significance difference in terms of BMI, HBV-DNA, Cirrhosis, TBIL, ALB, PLT, PT/INR, ALT, blood loss, intraoperative transfusion, and the six liver functional reserve models.

Significant univariable predictors for PHLF

Univariate logistic regression was performed on the aforementioned possible clinical risk factors (Table 2). The possible discriminating univariable factors for PHLF were BMI, HBV-DNA, TBIL, ALB, PLT, prothrombin time, INR, blood loss, while the most accurate one was prothrombin time (AUC: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.58-0.69).

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Variable | Total (n = 745) | Without PHLF (n = 642) | PHLF (n = 103) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, years | 53.0 (45.0-60.0) | 53.0 (44.0-60.0) | 54.0 (47.5-60.5) | 0.154 |

| Sex | 0.724 | |||

| Female | 121 (16.2%) | 106 (16.5%) | 15 (14.6%) | |

| Male | 624 (83.8%) | 536 (83.5%) | 88 (85.4%) | |

| BMI, Kg/m2 | 23.3 (21.5-24.8) | 23.3 (21.5-24.9) | 22.5 (21.2-24.2) | 0.038 |

| Diabetes | 0.060 | |||

| No | 694 (93.2%) | 601 (93.6%) | 93 (90.3%) | |

| Yes | 51 (6.8%) | 41 (6.4%) | 10 (9.7%) | |

| Underlying liver disease | ||||

| HBsAg | 0.492 | |||

| Negative | 165 (22.1%) | 139 (21.7%) | 26 (25.2%) | |

| Positive | 580 (77.9%) | 503 (78.3%) | 77 (74.8%) | |

| HBeAg | 0.511 | |||

| Negative | 600 (80.5%) | 520 (81.0%) | 80 (77.7%) | |

| Positive | 145 (19.5%) | 122 (19.0%) | 23 (22.3%) | |

| HBV-DNA, Log10 IU/mL | 0.00 (0.00-4.53) | 0.00 (0.00-4.47) | 3.00 (0.00-5.00) | 0.022 |

| Anti-HCV | 1.000 | |||

| No | 736 (98.8%) | 634 (98.8%) | 102 (99.0%) | |

| Yes | 9 (1.2%) | 8 (1.2%) | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Antiviral therapy | 0.280 | |||

| No | 604 (81.1%) | 523 (81.4%) | 81 (78.6%) | |

| Yes | 129 (17.3%) | 107 (16.7%) | 22 (21.4%) | |

| Data Missing | 12 (1.6%) | 12 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Radiological findings | ||||

| Ascites | 0.372 | |||

| No | 669 (89.8%) | 579 (90.2%) | 90 (87.4%) | |

| Mild | 76 (10.2%) | 63 (9.8%) | 13 (12.6%) | |

| Cirrhosis | 0.033 | |||

| No | 437 (58.7%) | 387 (60.3%) | 50 (48.5%) | |

| Yes | 308 (41.3%) | 255 (39.7%) | 53 (51.5%) | |

| Laboratory measurements | ||||

| TBIL, μmol/L | 13.4 (10.0-18.0) | 13.2 (10.0-17.6) | 15.0 (10.5-19.8) | 0.029 |

| ALB, g/L | 41.5 (39.0-44.0) | 42.0 (39.0-44.3) | 40.0 (38.0-42.5) | <0.001 |

| PLT, ×109/L | 182 (138-237) | 184 (141-240) | 164 (120-223) | 0.011 |

| PT, seconds | 12.0 (11.3-12.9) | 12.0 (11.2-12.7) | 12.4 (11.9-13.4) | <0.001 |

| INR | 1.00 (0.98-1.03) | 1.00 (0.98-1.03) | 1.00 (1.00-1.09) | 0.001 |

| ALT, U/L | 36.0 (24.0-52.4) | 35.0 (23.0-52.0) | 41.9 (26.3-65.0) | 0.012 |

| AST, U/L | 36.0 (23.0-58.0) | 35.0 (23.0-56.0) | 40.0 (25.0-63.0) | 0.069 |

| Cr, μmol/L | 68.0 (59.0-77.0) | 68.0 (59.0-76.8) | 67.0 (58.0-77.5) | 0.848 |

| Surgical factor | ||||

| Clamping time, min | 16.0 (9.00-22.0) | 16.0 (9.00-22.0) | 16.0 (10.0-20.0) | 0.411 |

| Blood loss, mL | 400 (200-800) | 350 (200-700) | 500 (200-1000) | 0.003 |

| Intraoperative transfusion | 0.005 | |||

| No | 519 (69.7%) | 460 (71.7%) | 59 (57.3%) | |

| Yes | 226 (30.3%) | 182 (28.3%) | 44 (42.7%) | |

| Tumor factor | ||||

| Tumor size, cm | 9.00 (5.85-12.7) | 9.00 (5.20-12.4) | 10.0 (7.00-13.0) | 0.064 |

| Tumor number | 0.487 | |||

| 1 | 626 (84.0%) | 543 (84.6%) | 83 (80.6%) | |

| 2 | 118 (15.9%) | 98 (15.3%) | 20 (19.4%) | |

| 3 | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Microvascular invasion | 0.280 | |||

| No | 289 (38.8%) | 254 (39.6%) | 35 (44.0%) | |

| Yes | 456 (61.2%) | 388 (60.4%) | 68 (66.0%) | |

| Differentiation | 0.173 | |||

| well | 7 (0.9%) | 7 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| moderate | 718 (96.4%) | 621 (96.7%) | 97 (94.2%) | |

| poor | 20 (2.7%) | 14 (2.2%) | 6 (5.8%) | |

| Liver functional reserve models | ||||

| ALBI | -2.80 (-3.00 - -2.56) | -2.81 (-3.01 - -2.58) | -2.66 (-2.88 - -2.44) | <0.001 |

| ALBI grade | 0.004 | |||

| 1 | 532 (71.4%) | 472 (73.5%) | 60 (58.3%) | |

| 2 | 212 (28.5%) | 169 (26.3%) | 43 (41.7%) | |

| 3 | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| MELD | 7.00 (6.00-7.00) | 7.00 (6.00-7.00) | 7.00 (6.00-8.00) | 0.007 |

| MELD grade | 0.007 | |||

| 1 | 588 (78.9%) | 517 (80.5%) | 71 (68.9%) | |

| 2 | 153 (20.5%) | 123 (19.2%) | 30 (29.1%) | |

| 3 | 4 (0.6%) | 2 (0.3%) | 2 (2.0%) | |

| PALBI | -2.56 (-2.73 - -2.37) | -2.56 (-2.74 - -2.38) | -2.50 (-2.65 - -2.33) | 0.026 |

| PALBI grade | 0.153 | |||

| 1 | 398 (53.4%) | 352 (54.8%) | 46 (44.7%) | |

| 2 | 290 (38.9%) | 243 (37.9%) | 47 (45.6%) | |

| 3 | 57 (7.7%) | 47 (7.3%) | 10 (9.7%) | |

| APRI | 0.52 (0.30-0.88) | 0.50 (0.29-0.85) | 0.62 (0.38-1.05) | 0.006 |

| APRI grade | 0.063 | |||

| 1 | 360 (48.3%) | 321 (50.0%) | 39 (37.9%) | |

| 2 | 321 (43.1%) | 269 (41.9%) | 52 (50.5%) | |

| 3 | 64 (8.6%) | 52 (8.1%) | 12 (11.6%) | |

| FIB4 | 1.79 (1.06-2.83) | 1.74 (1.04-2.77) | 2.04 (1.38-3.37) | 0.015 |

| FIB4 grade | 0.051 | |||

| 1 | 280 (37.6%) | 250 (38.9%) | 30 (29.1%) | |

| 2 | 320 (43.0%) | 275 (42.8%) | 45 (43.7%) | |

| 3 | 145 (19.4%) | 117 (18.3%) | 28 (27.2%) | |

| King's score | 11.0 (6.06-18.5) | 10.4 (5.88-17.8) | 14.0 (8.60-23.0) | <0.001 |

| King's grade | 0.001 | |||

| 1 | 258 (34.6%) | 235 (36.6%) | 23 (22.3%) | |

| 2 | 267 (35.8%) | 232 (36.1%) | 35 (34.0%) | |

| 3 | 220 (29.5%) | 175 (27.3%) | 45 (43.7%) | |

Abbreviations: PHLF, post-hepatectomy liver failure; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; BMI, body mass index; HBsAg, Hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg, Hepatitis B e-antigen; HBV-DNA, hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid; Anti-HCV, hepatitis C virus antibody; TBIL, total bilirubin; ALB, albumin; PLT, platelet; PT, prothrombin time; INR, international normalized ratio; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; Cr, creatinine; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; PALBI, platelet-albumin-bilirubin; APRI, AST to platelet ratio index; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; FIB4, fibrosis index based on 4 factors.

AUCs of univariable predictors for PHLF in HCC patients undergoing major hepatectomy

| Predictor | AUC | 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 0.54 | 0.48-0.61 | 0.154 |

| Sex (Male/Female) | 0.51 | 0.45-0.57 | 0.751 |

| BMI, Kg/m2 | 0.44 | 0.38-0.50 | 0.039 |

| Antiviral therapy (Yes/No) | 0.52 | 0.46-0.58 | 0.476 |

| Underlying liver disease | |||

| HBsAg (Positive/Negative) | 0.48 | 0.42-0.54 | 0.558 |

| HBeAg (Positive/Negative) | 0.52 | 0.46-0.58 | 0.587 |

| Anti-HCV (Positive/Negative) | 0.50 | 0.44-0.56 | 0.964 |

| HBV-DNA, U/mL | 0.58 | 0.52-0.64 | 0.016 |

| Radiological findings | |||

| Cirrhosis (Yes/No) | 0.56 | 0.50-0.62 | 0.056 |

| Ascites (Yes/No) | 0.51 | 0.45-0.56 | 0.875 |

| Laboratory measurements | |||

| TBIL, μmol/L | 0.57 | 0.51-0.62 | 0.029 |

| ALB, g/L | 0.39 | 0.33-0.45 | <0.001 |

| PLT, ×109/L | 0.42 | 0.36-0.48 | 0.011 |

| PT, seconds | 0.64 | 0.58-0.69 | <0.001 |

| INR | 0.60 | 0.55-0.66 | <0.001 |

| ALT, U/L | 0.58 | 0.52-0.64 | 0.012 |

| AST, U/L | 0.56 | 0.50-0.62 | 0.069 |

| Cr, μmol/L | 0.51 | 0.45-0.56 | 0.848 |

| Surgical factor | |||

| Blood loss, ml | 0.59 | 0.53-0.65 | 0.004 |

| Intraoperative transfusion (Yes/No) | 0.57 | 0.51-0.63 | 0.019 |

| Clamping time, min | 0.47 | 0.41-0.54 | 0.413 |

| Tumor factor | |||

| Tumor size, cm | 0.56 | 0.49-0.62 | 0.064 |

| Tumor number | 0.52 | 0.46-0.58 | 0.520 |

| Microvascular invasion | 0.53 | 0.48-0.58 | 0.281 |

| Differentiation | 0.53 | 0.49-0.57 | 0.173 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; PHLF, post-hepatectomy liver failure; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; HBsAg, Hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg, Hepatitis B e-antigen; HBV-DNA, hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid; Anti-HCV, hepatitis C virus antibody; TBIL, total bilirubin; ALB, albumin; PLT, platelet; PT, prothrombin time; INR, international normalized ratio; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; Cr, creatinine.

Evaluation of liver functional reserve models for PHLF

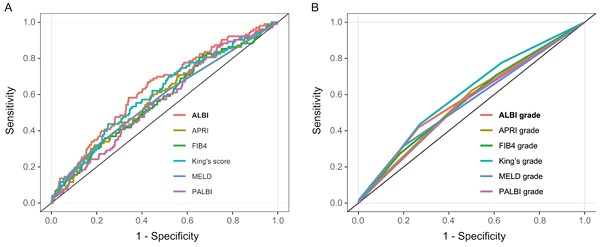

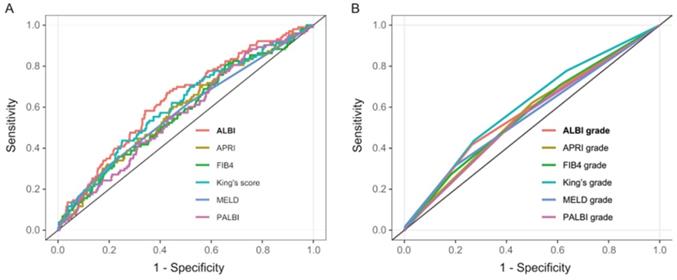

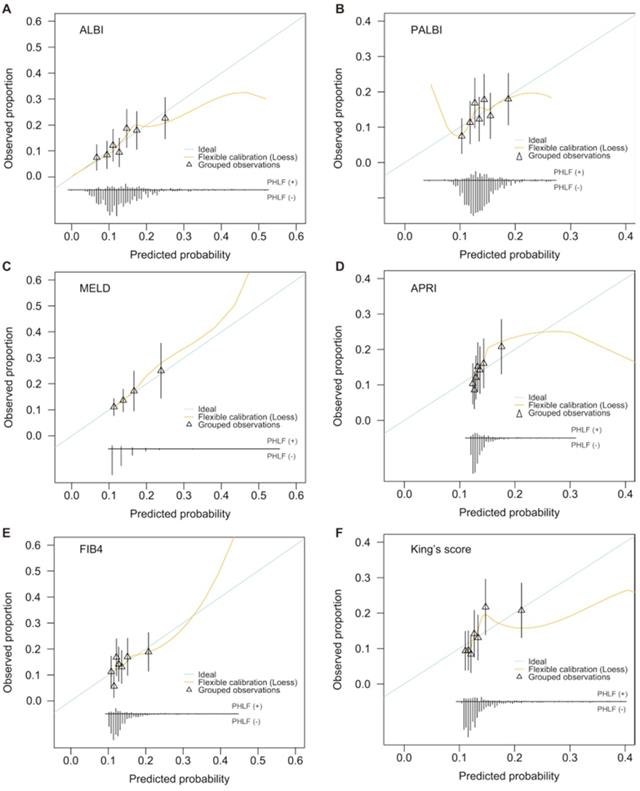

AUCs for the six models were as follows: ALBI AUC 0.64 (95% CI: 0.58-0.69), MELD AUC 0.58 (95% CI: 0.52-0.64), APRI AUC 0.59 (95% CI: 0.53-0.64), FIB4 AUC 0.57 (95% CI: 0.51-0.63), PALBI AUC 0.57 (95% CI: 0.51-0.63), and King's score AUC 0.61 (95% CI: 0.55-0.67) (Table 3 and Figure 2A). ALBI model had the greatest AUC for predicting PHLF. Furthermore, when the six models were categorized into 3 classifications, most of their prediction performance will declined with exception of King's score (Table 3 and Figure 2B). For all models, calibration appeared visually good (Figure 3).

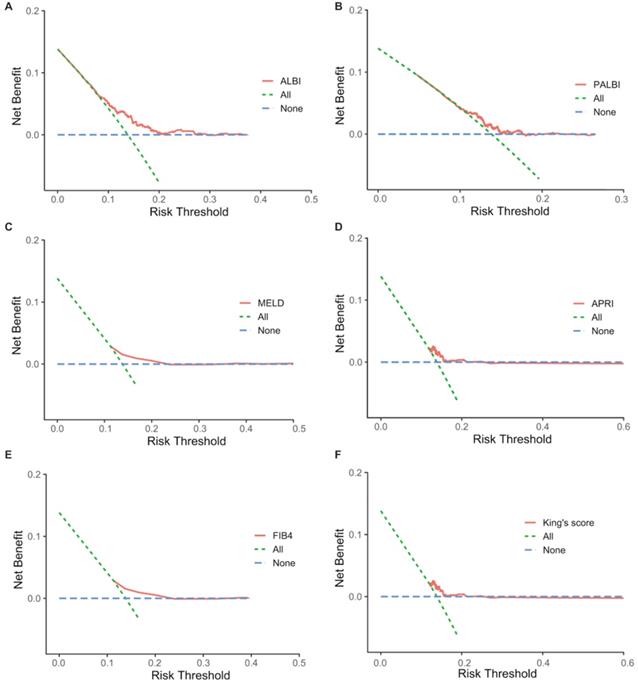

Decision curve analyses to assess clinical utility

This study compared net benefit for each model to the strategies of treating all patients, treating no patients for PHLF. Although all models showed greater net benefit than treating all patients at a limit range of threshold probabilities, the ALBI demonstrated net benefit across the largest range of threshold probabilities (Figure 4).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of six liver functional reserve models (A) and hierarchical models (B) predicting posthepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients who underwent major hepatectomy.

Calibration plots for six models estimating PHLF probabilities. A: ALBI; B: PALBI; C: MELD; D: APRI; E: FIB4; F: King's score.

Decision curve analysis comparing net benefit of each liver functional reserve model for PHLF. A: ALBI; B: PALBI; C: MELD; D: APRI; E: FIB4; F: King's score.

Discriminative ability of each liver functional reserve model in cohort

| Model | AUC | 95% CI | P value | DeLong's test for two correlated ROC curves |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALBI | 0.64 | 0.58-0.69 | <0.001 | Ref. |

| ALBI Grade 1/2/3 (<-2.6/-2.6 ≤ -1.39 /> -1.39) | 0.58 | 0.52-0.63 | 0.013 | <0.001 |

| PALBI | 0.57 | 0.51-0.63 | 0.026 | 0.005 |

| PALBI Grade 1/2/3 (≤ -2.53, -2.53-2.09, > -2.09) | 0.55 | 0.50-0.61 | 0.09 | 0.001 |

| APRI | 0.59 | 0.53-0.64 | 0.006 | 0.153 |

| APRI Grade, 1/2/3 (<0.5/0.5-1.5/>1.5) | 0.56 | 0.51-0.62 | 0.035 | 0.039 |

| MELD | 0.58 | 0.52-0.64 | 0.012 | 0.007 |

| MELD Grade, 1/2/3 (<8/8-12/>12) | 0.56 | 0.51-0.61 | 0.053 | 0.012 |

| FIB4 | 0.57 | 0.51-0.63 | 0.015 | 0.094 |

| FIB4 Grade 1/2/3 (<1.45/1.45-3.25/>3.25) | 0.57 | 0.51-0.62 | 0.028 | 0.062 |

| King's score | 0.61 | 0.55-0.67 | <0.001 | 0.395 |

| King's grade 1/2/3 (<7.6/7.6-16.7/16.7) | 0.60 | 0.55-0.66 | <0.001 | 0.351 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; PALBI, platelet-albumin-bilirubin; APRI, AST to platelet ratio index; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; FIB4, fibrosis index based on 4 factors.

Subgroup analysis

Finally, subpopulation analyses were done in the patients with or without cirrhosis to assess the overall performance of ALBI compared with the other 5 models. Subgroup analysis was presented in a forest plot (Figure S1). In cirrhotic patients, ALBI and PALBI had the better predictive accuracy (AUC = 0.63 and 0.60, respectively) compared with other 4 models. In subgroup patients without cirrhosis, ALBI, MELD, FIB4 and King's score had significant predictive accuracy (P = 0.012, 0.030, 0.011, 0.007 and AUC = 0.62, 0.59, 0.61 and 0.63, respectively).

Discussion

Liver failure is one of the leading causes of perioperative death in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after major hepatectomy. This study applied the “50-50 criteria” proposed by Silvio Balzan et al. in 2005 as a diagnostic criterion for liver failure. In our study, the incidence of liver failure after major liver resection is 13.8%, the 90-day mortality of patients with PHLF was significantly higher than the patients who did not experience liver failure (38.6% vs. 26.2%, P = 0.011) in our multi-institutional cohort. Selection criteria for major hepatectomy and prediction of the individual PHLF risk are debatable. Accurate assessment of preoperative liver reserve function is one of the keys to reducing the occurrence and death of liver failure after major liver resection [27]. Clinicians have been preferring to use new classification of objective indicators to assess liver function more accurately. Therefore, MELD, APRI, FIB4, King's score, ALBI and PALBI models have been proposed successively. This study aimed at evaluating these six common models of PHLF in HCC patients undergoing major hepatectomy.

In this article, 745 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent major hepatectomy were retrospectively analyzed. As for univariable risk factor, BMI, HBV-DNA, TBIL, ALB, PLT, prothrombin time, INR, and blood loss were predictors for PHLF. Thus, the factors which were related to patients' demographic, HBV-related, liver related and surgical factors have been shown the associations with PHLF. The result was partially consistent with Kauffmann et al. and Shoup et al. who validate TBIL and coagulation as risk factors of PHLF [28-29].

As an integrated variable, ALBI indicated the best predictive accuracy, regardless of having cirrhosis or not. Although these models are calculated using objective indicators, the numerical results and the accuracy of predictions vary a lot. The ALBI model proposed in 2015 was simply calculated from two indicators, ALB and TBIL, and many literatures have confirmed its accuracy in assessing liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma [30-31]. At the same time, ALBI and King's score models were equally statistically significant in predicting PHLF after major liver resection (P = 0.395). As verified by this article, for HCC patients undergoing major hepatectomy, the ALBI model has a better ability to predict PHLF then PALBI (P = 0.005) and MELD (P = 0.007). This result was in accordance with the study reported by Alexander M. that ALBI can predict PHLF better than MELD after hepatectomy [21]. Subgroup analysis was then performed based on patients with or without cirrhosis. For cirrhotic patients, except ALBI, PALBI may be also a good choice for predicting PHLF. Moreover, for patients without cirrhosis, ALBI, MELD, FIB4 and King's score may be more suitable.

The strengths of this study lie in the large patient population. However, the present study has some limitations. First, it is a retrospective study with inherent shortcoming. Second, although our data are from four well-known hospitals, they are all from Chinese people, whether our conclusion is suitable in patients from the West remains uncertain. Third, there is no data on remnant liver volume and ICG-15, which may be useful in predicting PHLF. Further external validation of our results is needed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, among the six liver functional reserve models (ALBI, APRI, FIB4, MELD, PALBI, King's score), the ALBI exhibits more accurate predictive ability for PHLF in HCC patients undergoing major hepatectomy, regardless of having cirrhosis or not.

Abbreviations

PHLF: post-hepatectomy liver failure; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; CTP: Child-Turcotte-Pugh classification; ALBI: albumin-bilirubin; PALBI: platelet-albumin-bilirubin; APRI: AST to platelet ratio index; MELD: model for end-stage liver disease; FIB4: fibrosis index based on 4 factors; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus; BMI: body mass index; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg: Hepatitis B e-antigen; HBV-DNA: hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid; Anti-HCV: hepatitis C virus antibody; TBIL: total bilirubin; ALB: albumin; PLT: platelet; PT: prothrombin time; INR: international normalized ratio; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; Cr: creatinine; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; ROC: Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve; AUC: area under the curve; IQR: interquartile range.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figure and table.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [81871988 to C.Z.J.], the Jiangsu Province Key Research and Development Program [BE2019747 to C.Z.J.], and the Six Talent Peaks Project of Jiangsu Province [SWYY-007 to C.Z.J.].

Ethics approval statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committees of the Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital, Zhongda Hospital Southeast university, Qin Huai Medical District of Eastern Theater General Hospital and the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiao Tong University. The informed consent was obtained from each patient for using their data in the research.

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Author Contributions

- Conception and design: Zhangjun Cheng, Zhengqing Lei, Guangmeng Guo.

- Financial support: Zhangjun Cheng.

- Collection and assembly of data: all authors.

- Data analysis and interpretation: all authors.

- Manuscript writing: all authors.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Josep ML, Jessica ZR, Eli Pikarsky, Bruno Sangro, Myron Schwartz, Morris Sherman. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16018

2. Rahbari NN, Garden OJ, Padbury R, Brooke-Smith M, Crawford M, Adam R. et al. Posthepatectomy liver failure: a definition and grading by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS). Surgery. 2011;149:713-724

3. Van den Broek MA, Olde Damink SW, Dejong CH, Lang H, Malago M, Jalan R. et al. Liver failure after partial hepatic resection: definition, pathophysiology, risk factors and treatment. Liver Int. 2008;28:767-780

4. Li B, Qin YY, Qiu ZQ, Ji J, Jiang XQ. A cohort study of hepatectomy-related complications and prediction model for postoperative liver failure after major liver resection in 1,441 patients without obstructive jaundice. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(4):305

5. Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL. et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:464-470

6. Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Barrat A, Askari F, Conjeevaram HS, Su GL. et al. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of 7 staging systems in an American cohort. Hepatology. 2005;41:707-716

7. Alghamdi T, Abdel-Fattah M, Zautner A, Lorf T. Preoperative model for end-stage liver disease score as a predictor for posthemihepatectomy complications. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:668-675

8. Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS. et al. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518-526

9. Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B, Verkarre V, Nalpas A, Dhalluin-Venier V. et al. FIB-4: an inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. comparison with liver biopsy and fibrotest. Hepatology. 2007;46:32-36

10. Kim WR, Berg T, Asselah T, Flisiak R, Fung S, Gordon SC. et al. Evaluation of APRI and FIB-4 scoring systems for non-invasive assessment of hepatic fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B patients. J Hepatol. 2016;64:773-780

11. Said M, Soliman Z, Daebes H, S ME-N, El-Serafy M. Real life application of FIB-4 & APRI during mass treatment of HCV genotype 4 with directly acting anti-viral agents in Egyptian patients, an observational study. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13:1189-1195

12. Cross TJ, Rizzi P, Berry PA, Bruce M, Portmann B, Harrison PM. King's Score: an accurate marker of cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:730-738

13. Zhang ZQ, Xiong L, Zhou JJ, Miao XY, Li QL, Wen Y. et al. Ability of the ALBI grade to predict posthepatectomy liver failure and long-term survival after liver resection for different BCLC stages of HCC. World Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2018 16(1)

14. Xu Y, Hu XL, Li JB, Dong R, Bai XX. An improved scoring system based on PALBI in predicting post-hepatectomy liver failure outcomes. Dig Dis. 2020 39(3)

15. Fu R, Qiu TT, Ling WW, Luo Y. Comparison of preoperative two-dimensional shear wave elastography, indocyanine green clearance test and biomarkers for post hepatectomy liver failure prediction in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21(1):142

16. Pang Q, Bi JB, Xu XS, Liu SS, Zhang JY, Zhou YY. et al. King's score as a novel prognostic model for patients with hepatitis B-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27(11):1337-1346

17. Johnson PJ, Berhane S, Kagebayashi C, Satomura S, Teng M, Reeves HL. et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:550-558

18. Roayaie S, Jibara G, Berhane S, Tabrizian P, Park JW, Yang J. et al. PALBI-An Objective Score Based on Platelets, Albumin & Bilirubin Stratifies HCC Patients Undergoing Resection & Ablation Better than Child's Classification. The Liver Meeting: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. 2015 110095

19. Liu PH, Hsu CY, Hsia CY, Lee YH, Chiou YY, Huang YH. et al. ALBI and PALBI grade predict survival for HCC across treatment modalities and BCLC stages in the MELD Era. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:879-886

20. Wang YY, Zhong JH, Su ZY, Huang JF, Lu SD, Xiang BD. et al. Albumin-bilirubin versus Child-Pugh score as a predictor of outcome after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2016;103:725-734

21. Fagenson AM, Gleeson EM, Pitt HA, Lau KN. Albumin-Bilirubin Score vs Model for End-Stage Liver Disease in Predicting Post-Hepatectomy Outcomes. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2020;230(4):637-645

22. Andreatos N, Amini N, Gani F, Margonis GA, Sasaki K, Thompson VM. et al. Albumin-Bilirubin Score: Predicting Short-Term Outcomes Including Bile Leak and Post-hepatectomy Liver Failure Following Hepatic Resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:238-248

23. Bozin T, Mustapic S, Bokun T, Patrlj L, Rakic M, Aralica G. et al. Albi Score as a Predictor of Survival in Patients with Compensated Cirrhosis Resected for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Exploratory Evaluation in Relationship to Palbi and Meld Liver Function Scores. Acta Clin Croat. 2018;57:292-300

24. Cheng Z, Yang P, Qu S, Zhou J, Yang J, Yang X. et al. Risk factors and management for early and late intrahepatic recurrence of solitary hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. HPB (Oxford). 2015;17:422-427

25. Balzan S, Belghiti J, Farges O, Ogata S, Sauvanet A, Delefosse D. et al. The “50-50 criteria” on postoperative day 5: an accurate predictor of liver failure and death after hepatectomy. Ann Surg. 2015;242(6):824-829

26. Marshall Brown. A tutorial for R package rmda: Risk Model Decision Analysis. 2018; mdbrown.github.io.rmda:1-22.

27. Seong KN, Sun YY, Sang JS, Young KJ, Ji HK, Yeon SS. et al. ALBI versus Child-Pugh grading systems for liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2018:1-10

28. Kauffmann R, Fong Y. Post-hepatectomy liver failure. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2014;3:238-246

29. Shoup M. Volumetric Analysis Predicts Hepatic Dysfunction in Patients Undergoing Major Liver Resection. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2003;7:325-330

30. Connie HM Ho, Chi-Leung Chiang, Francis AS Lee, Horace CW Choi, Jeffery CH Chan, Cynthia SY Yeung. et al. Comparison of platelet-albumin-bilirubin (PALBI), albuminbilirubin (ALBI), and child-pugh (CP) score for predicting of survival in advanced hcc patients receiving radiotherapy (RT). Oncotarget. 2018;9(48):28818-28829

31. Pinato DJ, Sharma R, Allara E, Yen C, Arizumi T, Kubota K. et al. The ALBI grade provides objective hepatic reserve estimation across each BCLC stage of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;66(2):338-346

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Zhangjun Cheng, MD, Hepato-pancreato-biliary center, Zhongda Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing 210009, China. Tel: 0086-25-83262323; Fax: 0086-25-83272011; E-mail: chengzhangjunedu.cn.

Corresponding author: Zhangjun Cheng, MD, Hepato-pancreato-biliary center, Zhongda Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing 210009, China. Tel: 0086-25-83262323; Fax: 0086-25-83272011; E-mail: chengzhangjunedu.cn.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact