Impact Factor

ISSN: 1837-9664

J Cancer 2015; 6(2):111-119. doi:10.7150/jca.10867 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Identification of Stably Expressed lncRNAs as Valid Endogenous Controls for Profiling of Human Glioma

Center for Neuropathology and Prion Research (ZNP), Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Feodor-Lynen-Str. 23, D-81377 Munich, Bavaria, Germany.

Received 2014-10-21; Accepted 2014-11-21; Published 2015-1-1

Abstract

Background: Recent research indicates that long non-coding RNAs (lncRNA) represent a new family of RNAs that is of fundamental importance for controlling transcription and translation. Thereby, there is increasing evidence that lncRNAs are also important in tumourigenesis. Thereby valid expression profiling using quantitative PCR requires suitable, stably expressed normalisers to achieve reliable and reproducible data. However, no systematic analysis of suitable references in lncRNA studies in human glioma has been performed yet.

Methods: In this study, we investigated 90 lncRNAs in 30 tissue specimen for the expression stability in human diffuse astrocytoma (WHO-Grade II), anaplastic astrocytoma (WHO-Grade III) and glioblastoma (WHO-Grade IV) both alone as well as in comparison with normal white matter. Our identification procedure included a rigorous bioinformatical selection process that resulted in the inclusion of only highly abundant, equally expressed lncRNAs for further analysis. Additionally, lncRNAs were classified according to their stability value using the NormFinder algorithm.

Results: We identified 24 appropriate normalisers suitable for studies in diffuse astrocytoma, 22 for studies in anaplastic astrocytoma and 12 for studies in glioblastoma. Comparing all three glioma entities 7 lncRNAs showed stable expression levels. Addition of normal brain tissue resulted in only 4 suitable lncRNAs.

Conclusions: Our findings indicate that 4 lncRNAs (HOXA6as, H19 upstream conserved 1 and 2, Zfhx2as and BC200) are suitable as normalisers in glioma and normal brain. These lncRNAs may thus be regarded as universal references being applicable for the accurate normalisation of lncRNA expression profiling in various glioma (WHO-Grades II-IV) alone and in combination with brain tissue. This enables to perform valid longitudinal studies, e.g. of glioma before and after malignisation to identify changes of lncRNA expressions probably driving malignant transformation.

Keywords: long non-coding RNA, lncRNA, Glioma, References, qPCR, Profiling.

Introduction

Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) has recently been observed not being just by-product in the process of transcription but being of significant importance in transcriptional and translational control as well as during splicing, cell cycle, apoptosis, pluripotency, reprogramming and imprinting [1-8]. This highlights a potential role of lncRNAs during tumour formation and progression. Nevertheless, only a minority of lncRNAs has so far been investigated and functionally annotated. [1, 9]. According to Ma et al. lncRNAs can be classified by (1) genomic location, (2) exerted effect on DNA sequences, (3) functional mechanisms and (4) targeting mechanisms [10]. One of the best studied processes being associated with lncRNAs is the X-chromosome inactivation: A single X-inactivation center (Xic) of about 100-500 kbps in length [11, 12] is necessary and sufficient for X-chromosome inactivation [11, 13]. Thereby, Xic contains a well characterised lncRNA: Xist (X-inactive specific transcript). This is a 17-20 kbps long RNA that tags the X-chromosome during early X-chromosome inactivation [11, 12]. Subsequently, only the X-chromosome that expresses Xist is inactivated [11, 14-18]. It is obvious that disturbances in such powerful regulation mechanisms can propagate the development of numerous human diseases.

Especially in the context of tumourigenesis, distinct lncRNAs have been highlighted [19, 20]: HOTAIR (HOX antisense intergenic RNA) is a lncRNA being expressed in various cancers interacting with PRC2 (Polycomb repressive complex 2) [21]. Studies have shown that HOTAIR is associated with motility, invasion, and metastatic potential in tumours [22]. HOTTIP is another example of a lncRNA that is potentially associated with the differentiation status of cancer cells that may be regarded as a co-factor leading to genomic rearrangements in cancer [20, 23, 24]. In case of the antisense lncRNA ANRIL studies have shown that ANRIL is able to repress tumour suppressor loci and thus may promote cancer [25].

There is recent evidence, that lncRNAs may also play a crucial role in brain tumours [26-28]. Glioblastoma (GBM, WHO-Grade IV) represent not only the most frequent brain tumour entity of adults but also the most fatal one with a high risk of recurrence and a very dismal prognosis [29]. Thereby, primary and secondary GBMs can be distinguished: Whilst primary GBMs are tumours that originate de novo, secondary GBMs are tumours that derive from lower-grade gliomas, i.e. diffuse astrocytoma (DA, A II, WHO-Grade II) and anaplastic astrocytoma (AA, A III, WHO-Grade III) in a process of malignant transformation [29-31].

Especially by investigating changes in gliomas occurring during tumour progression, i.e. DA, AA, GBM, the selection of suitable references for expression profiling is a challenge. “Ideal” references are genes that do not show expression changes in all investigated tumour entities. They have to be identified and validated prior to quantitative data analysis for each tissue type under the desired experimental setup [32, 33]. As the stability and integrity of different RNA classes, e.g. mRNA, rRNA, miRNA, is highly variable [32-37] normalisers should ideally be composed of the same RNA class as the target RNAs to avoid computational errors by referring to different RNA classes.

So far, there are no lncRNA normalisers for quantitative PCR (qPCR) data in human gliomas available. Moreover, the importance to use a combination of at least two or more validated reverences for proper evaluation of data has not yet been considered [34-37]. This problem is now solved by us. In this study, we investigate 90 different lncRNAs in parallel on human diffuse astrocytoma, anaplastic astrocytoma, glioblastoma and normal white matter as “healthy”, unaffected brain tissue. We determined stably expressed lncRNAs using the NormFinder algorithm for both each entity alone as well as in combination and in comparison with normal brain tissue. This way, we were able to identify stably expressed lncRNAs suitable as universal normalisers in studies investigating astrocytoma of different WHO-Grade, enabling longitudinally designed studies of tumours before and after malignant transformation.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection

For this study, we selected 30 different tissue specimen including five human diffuse astrocytoma (WHO-Grade II), five anaplastic astrocytoma (WHO-Grade III), and 15 glioblastoma (WHO-Grade IV) as well as 5 human occipital white matter specimens as “healthy” brain tissue.

Tumour samples were provided by the Brain Tumour Bank of the Center for Neuropathology. Written informed consent was obtained according to the guidelines of the local ethics committee. Surgical samples were fixed with 4% buffered formalin, paraffin embedded, and subjected to routine histological stains: H&E (Haematoxylin and Eosin), EvG (Elastic van Gieson), PAS (Periodic acid-Schiff), Gomori silver stain and immunohistochemistry using antibodies against GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein, monoclonal mouse antibody, clone 6F2, Dako), MAP2 (microtubule-associated protein 2, clone HM.2, Sigma) and Ki67 (monoclonal mouse antibody, clone MIB1, Dako). Tumour samples were classified according to the WHO (world health organisation) classification of tumours of the central nervous system, 4th edition, 2007 [29-31]. Determination of IDH1 (isocitrate dehydrogenase 1) mutations was performed using the pyrosequencing technique as described previously [38]. MGMT promoter methylation was determined as described previously [39]. LOH1p/19q (loss of heterozygousity of chromosome 1p and 19q) was detected as described previously [40]. Detailed information of patients can be found in Table 1.

Tumour sample collection. Listed are all tumour samples used in this study including patient age at surgery, sex, tumour entity according to WHO-Grade, localisation and molecular genetic features of tumours. MGMT status: 0: not methylated; 1: methylated; 2: partially methylated; 9: not analysed due to low amount of tissue; IDH1-mutation: 0: wt; 1: R132H, 2: R132G; 3: R132C; 9: not analysed due to low amount of tissue; LOH1p/19q: 0: no; 1: 1p; 2: 19q; 3: 1p19q; 4: loss of some markers of 1p; 5: loss of some markers of 19q; 6: loss of some markers of 1p/19q; 9: not analysed due to low amount of tissue.

| Sample | Age at surgery [y] | Sex | Tumor Entity | WHO-Grade | Localisation of tumor | MGMT status | IDH1-mutation | LOH1p/19q |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AII_1 | 34 | f | Diffuse astrocytoma | II | frontal left | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| AII_2 | 34 | m | Diffuse astrocytoma | II | fronto-temporal right | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| AII_3 | 34 | m | Diffuse astrocytoma | II | intraparenchymatous | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| AII_4 | 39 | f | Diffuse astrocytoma | II | frontal right | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| AII_5 | 28 | f | Diffuse astrocytoma | II | precentral right | 1 | 9 | 2 |

| AIII_1 | 21 | f | Anaplastic astrocytoma | III | frontal right | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| AIII_2 | 50 | f | Anaplastic astrocytoma | III | frontal right | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AIII_3 | 25 | m | Anaplastic astrocytoma | III | intraparenchymatous | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| AIII_4 | 40 | m | Anaplastic astrocytoma | III | temporal left | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| AIII_5 | 39 | m | Anaplastic astrocytoma | III | temporoparietal left | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| GBM_1 | 49 | f | Glioblastoma | IV | frontal right | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| GBM_2 | 45 | f | Glioblastoma | IV | frontal right | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| GBM_3 | 41 | m | Glioblastoma | IV | frontal left | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| GBM_4 | 43 | m | Glioblastoma | IV | temporal right | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| GBM_5 | 54 | m | Glioblastoma | IV | intraparenchymatous | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| GBM_6 | 50 | m | Glioblastoma | IV | temporoparietal left | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| GBM_7 | 44 | m | Glioblastoma | IV | frontal left | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| GBM_8 | 46 | m | Glioblastoma | IV | temporal right | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| GBM_9 | 61 | m | Glioblastoma | IV | parietal left | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GBM_10 | 55 | f | Glioblastoma | IV | bifrontal | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| GBM_11 | 45 | m | Glioblastoma | IV | frontal left | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| GBM_12 | 72 | f | Glioblastoma | IV | temporal | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| GBM_13 | 73 | m | Glioblastoma | IV | temporal left | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| GBM_14 | 67 | m | Glioblastoma | IV | occipital right | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GBM_15 | 34 | f | Glioblastoma | IV | frontal left | 1 | 0 | 2 |

Control sample collection. Listed are all control samples used in this study including age of patients, sex, post-mortem intervals (PMI), investigated brain region and cause of death.

| Sample | Age [y] | Sex | PMI [h] | Region | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WM_1 | 63 | m | 18 | Occipital white matter | Cardiac arrest |

| WM_2 | 75 | m | 27 | Occipital white matter | Cardiac arrest |

| WM_3 | 77 | f | 20 | Occipital white matter | Cardiac arrest |

| WM_4 | 53 | m | 22 | Occipital white matter | Cardiac arrest |

| WM_5 | 55 | f | 14 | Occipital white matter | Cardiac arrest |

Human control tissue was provided by the Neurobiobank Munich (NBM). All investigated cases were collected and clinically as well as neuropathologically characterized according to the NBM standard protocols established by BrainNet Europe and BrainNet Germany. Patients did not show any neurological or psychiatric disorders. Written informed consent was obtained according to the guidelines of the local ethics committee. Detailed information of selected cases can be found in Table 2.

Extraction of RNA

Representative H&E stained slides of FFPE tumour samples were prepared and solid, viable tumour consisting of at least 90% tumour cells was microscopically identified. RNA extraction was performed on distinct, micro-dissected tumour regions.

In case of normal brain tissue, subcortical, occipital white matter was marked on H&E stained slides and isolation of distinct regions was performed similar to tumour samples. Extraction of RNA was performed using the RNeasy FFPE Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Quantity and quality of RNA was determined using a NanoDrop system determining the 260/280 nm absorbance ratio. In all cases the ratio was between 1.90 and 2.20. In order to avoid amplification bias we did not use pre-amplification of RNA but proceeded directly with subsequent analysis.

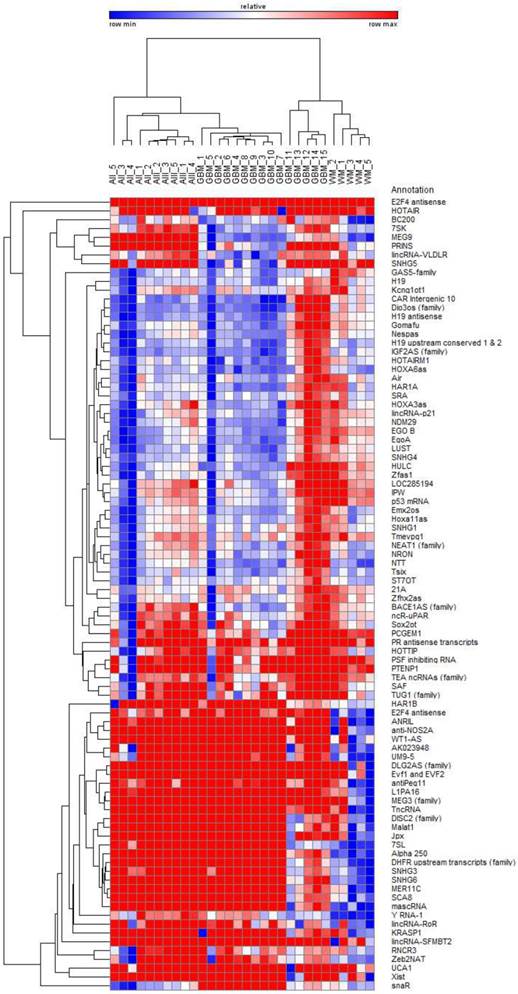

Bi-hierarchical clustering of all 90 investigated lncRNAs in 30 tissue specimen. We investigated 5 diffuse astrocytomas (A II, DA, WHO-Grade II), 5 anaplastic astrocytomas (A III, AA, WHO-Grade III), and 15 glioblastomas (GBM, WHO-Grade IV) as well as 5 occipital white matter tissues (WM) as healthy control. There is a clear clustering of tumour entities visible. Blue: low Ct-value; red: high Ct-value.

Polyadenylation reaction, reverse transcription and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

Polyadenylation and reverse transcription reactions were performed using the human LncProfiler qPCR Assay Kit (SBI). Equal amounts of RNA (750 ng) were used in the polyadenylation reaction. All procedures were performed according to the optimised manufacturer's protocols. Quantification of lncRNAs was performed using the validated pre-designed qPCR primer library of the human lncProfiler qPCR Assay Kit (SBI) allowing the parallel investigation of 90 annotated lncRNAs that are listed in the lncRNA database. Quantitative PCR was performed on a LightCycler 480 II device (Roche) using the SensiFAST SYBR No-ROX Kit (Bioline) and standard protocols.

Bioinformatical analysis

Clustering of expression data was performed using Gene-E software (http://www.broadinstitute.org/cancer/software/GENE-E/) and an un-supervised bi-hierarchical clustering algorithm based on pair-wise distance calculations. For the identification of stably expressed lncRNAs, cycle-threshold (Ct) values were used as basis for statistical analysis. To enhance reliability of data, only highly abundant lncRNAs (i.e. with Ct values < 30) were taken into consideration, lncRNAs with Ct values ≥ 30 were excluded due to low abundance and thus being not suitable as references. Furthermore, all lncRNAs that showed significant expression differences within different groups were excluded. For significance testing, GraphPad Prism software was used. We performed unpaired t-tests, p-values < 0.05 were considered as significant. Remaining lncRNAs were classified using the NormFinder algorithm taking both intra- and intergroup variations into consideration [41]. Only lncRNAs with stability values of < 0.1 were considered as appropriate.

Results

Each glioma entity shows different but distinct lncRNA profiles clearly separated from normal white matter

The analysis of 90 lncRNAs in 5 diffuse astrocytomas, 5 anaplastic astrocytomas, 15 glioblastomas and 5 normal white matter brain specimens show in an unsupervised bi-hierarchical clustering distinct lncRNA expression profiles (Figure 1): All diffuse astrocytomas build a distinct cluster that is flanked by anaplastic astrocytomas on one side. All anaplastic astrocytomas show another distinct cluster that is located between diffuse astrocytomas and glioblastomas. All glioblastomas cluster together and are flanked by anaplastic astrocytomas. Furthermore, all normal white matter specimens show a distinct cluster that is separated from all glioma clusters. The different clustering of lncRNA profiles emphasised that (1) lncRNA profiles of all tumour entities are individual representing different molecular pathways being activated in the tumours, (2) there is a step-wise change of lncRNA profiles that is represented by the clustering of diffuse astrocytomas being situated next to anaplastic astrocytomas that are situated next to glioblastomas and (3) separation of lncRNA profiles of different glioma entities mirrors the need for normalisers being equally expressed not only within one cluster but in all clusters to perform longitudinal studies on tumour specimen during tumour progression.

Identification of reference lncRNAs in diffuse astrocytoma, anaplastic astrocytoma and glioblastoma

The conscious analysis of lncRNA expression data was performed in a step-wise bioinformatical approach. To get reliable references, only highly abundant lncRNAs were taken into consideration, i.e. lncRNAs with Ct values of ≥ 30 were excluded due to low abundance indicating not being suitable as normalisers. All remaining lncRNAs were alaysed using the NormFinder algorithm [41] and ranked according to their stability values. Only lncRNAs with stability values of < 0.1 were considered as suitable normalisers.

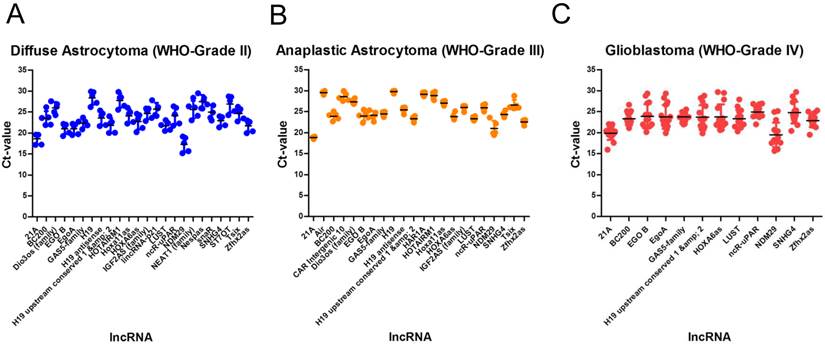

We identified 24 lncRNAs suitable as normalisers in diffuse astrocytomas (Table 3, Figure 2A). The top five are Zfhx2as (stability value 0.008), H19 (stability value 0.010), EgoA (stability value 0.010), IGF2AS (stability value 0.010) and Hoxa11as (stability value 0.012). In case of anaplastic astrocytomas, we identified 22 suitable normalisers (Table 3, Figure 2B), the five most stable lncRNAs are SNHG4 (stability value 0.005), H19 upstream conserved 1 and 2 (stability value 0.006), Dio3os (stability value 0.010), Hoxa11as (stability value 0.011) and IGF2AS (stability value 0.013). In glioblastoma we identified 12 suitable lncRNAs (Table 3, Figure 2C), the top five are LUST (stability value 0.016), SNHG4 (stability value 0.019), EgoA (stability value 0.034), H19 upstream conserved 1 and 2 (stability value 0.035) and EGO B (stability value 0.036).

Stably expressed lncRNAs in single glioma entities. We identified 24 suitable normalisers in diffuse astrocytoma (WHO-Grade II), 22 suitable normalisers in anaplastic astrocytoma (WHO-grade III) and 12 suitable normalisers in glioblastoma (WHO-Grade IV). All lncRNAs are arranged according to their stability values. Stability values are calculated using the NormFinder algorithm.

| Diffuse Astrocytoma (WHO-Grade II) | Anaplastic Astrocytoma (WHO-Grade III) | Glioblastoma (WHO-Grade IV) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene name | Stability value | Standard error | Gene name | Stability value | Standard error | Gene name | Stability value | Standard error |

| Zfhx2as | 0.008 | 0.004 | SNHG4 | 0.005 | 0.004 | LUST | 0.016 | 0.005 |

| H19 | 0.010 | 0.004 | H19 ups. cons. 1, 2 | 0.006 | 0.004 | SNHG4 | 0.019 | 0.005 |

| EgoA | 0.010 | 0.004 | Dio3os (family) | 0.010 | 0.005 | EgoA | 0.034 | 0.007 |

| IGF2AS (family) | 0.010 | 0.004 | Hoxa11as | 0.011 | 0.005 | H19 ups. cons. 1, 2 | 0.035 | 0.008 |

| Hoxa11as | 0.012 | 0.005 | IGF2AS (family) | 0.013 | 0.005 | EGO B | 0.036 | 0.008 |

| SNHG4 | 0.013 | 0.005 | HOXA6as | 0.013 | 0.005 | Zfhx2as | 0.041 | 0.009 |

| ST7OT | 0.015 | 0.006 | H19 | 0.013 | 0.006 | ncR-uPAR | 0.045 | 0.009 |

| HOTAIRM1 | 0.015 | 0.006 | HAR1A | 0.013 | 0.006 | 21A | 0.048 | 0.010 |

| Nespas | 0.016 | 0.006 | H19 antisense | 0.014 | 0.006 | HOXA6as | 0.051 | 0.010 |

| 21A | 0.017 | 0.006 | LUST | 0.016 | 0.006 | GAS5-family | 0.065 | 0.013 |

| H19 antisense | 0.018 | 0.007 | Air | 0.017 | 0.007 | NDM29 | 0.067 | 0.013 |

| snaR | 0.018 | 0.007 | 21A | 0.019 | 0.007 | BC200 | 0.086 | 0.017 |

| Tsix | 0.019 | 0.007 | CAR Intergenic 10 | 0.020 | 0.008 | |||

| Dio3os (family) | 0.019 | 0.007 | ncR-uPAR | 0.024 | 0.009 | |||

| EGO B | 0.021 | 0.008 | GAS5-family | 0.025 | 0.009 | |||

| LUST | 0.025 | 0.009 | EgoA | 0.027 | 0.010 | |||

| HOXA6as | 0.025 | 0.009 | HOTAIRM1 | 0.029 | 0.011 | |||

| lincRNA-p21 | 0.026 | 0.009 | EGO B | 0.030 | 0.011 | |||

| GAS5-family | 0.027 | 0.010 | BC200 | 0.034 | 0.012 | |||

| H19 ups. cons. 1, 2 | 0.029 | 0.010 | Zfhx2as | 0.037 | 0.013 | |||

| ncR-uPAR | 0.029 | 0.010 | Tsix | 0.053 | 0.019 | |||

| NEAT1 (family) | 0.030 | 0.011 | NDM29 | 0.069 | 0.025 | |||

| BC200 | 0.042 | 0.015 | ||||||

| NDM29 | 0.045 | 0.016 | ||||||

Identification of stable lncRNAs in diffuse astrocytoma in different glioma entities. In diffuse astrocytoma (WHO-Grade II) we identified 24 (A), in anaplastic astrocytoma (WHO-grade III) we identified 22 (B) and in glioblastoma (WHO-Grade IV) we identified 12 lncRNAs suitable as normalisers (C). Indicated are mean and SD.

Stably expressed lncRNAs suitable for studies in different human glioma entities. We identified 7 lncRNAs that are suitable for studies in multiple glioma entities. All lncRNAs are arranged according to their stability values. Intragroup and intergroup variations indicated were calculated using the NormFinder algorithm.

| Glioma | Intragroup variation | Intergroup variation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene name | Stability value | A II | A III | GBM | A II | A III | GBM |

| Zfhx2as | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | -0.006 | 0.005 |

| SNHG4 | 0.017 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | -0.013 | 0.001 | 0.013 |

| HOXA6as | 0.018 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.005 | -0.007 |

| H19 ups. cons. 1, 2 | 0.019 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | -0.017 | 0.004 | 0.013 |

| ncR-uPAR | 0.024 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | -0.004 | 0.023 | -0.019 |

| 21A | 0.025 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.005 | -0.027 | 0.021 |

| BC200 | 0.029 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.027 | 0.000 | -0.027 |

Expression stability of lncRNA references suitable for comparison of gliomas and normal brain tissue

To investigate gliomas during malignant transformation it is important to perform longitudinally designed studies that include tumour specimen before and after malignant transformation. To identify lncRNA normalisers that are applicable for diffuse astrocytoma, anaplastic astrocytoma and glioblastoma, we applied an extended bioinformatical approach: (1) Exclusion of low abundant lncRNAs with Ct values of ≥ 30, (2) exclusion of all lncRNAs with stability values of ≥ 0.1 in NormFinder analysis and (3) exclusion of all lncRNAs with significantly different expression levels (p < 0.05) in significance testing in order to consider both intragroup and intergroup variations during selection process.

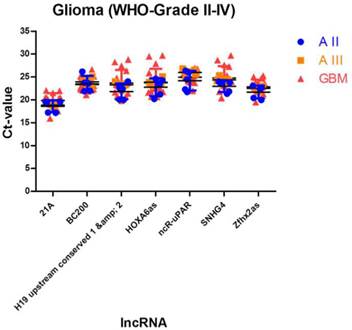

We identified 7 lncRNAs that fulfilled all criteria to be considered as stably expressed in all investigated tumour entities (Table 4, Figure 3). The five most stable lncRNAs are Zfhx2as (stability value 0.014), SNHG4 (stability value 0.017), HOXA6as (stability value 0.018), H19 upstream conserved 1 and 2 (stability value 0.019) and ncR-uPAR (stability value 0.024).

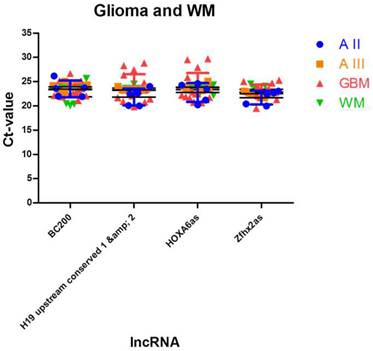

To identify lncRNAs being suitable as normalisers in different glioma entities and in normal brain tissue, we further enhanced our analysis by adding expression data of normal white matter. We applied the similar approach as in case of multiple glioma entities and found four stably expressed lncRNAs (Table 5, Figure 4): HOXA6as (stability value 0.019), H19 upstream conserved 1 and 2 (stability value 0.024), Zfhx2as (stability value 0.030) and BC200 (stability value 0.044). These lncRNAs may be regarded as universal normalisers being applicable in a broad range of studies focussing on human glioma research.

Stably expressed lncRNAs suitable for studies comparing different glioma entities. We identified 7 lncRNAs that are suitable as normalisers in studies investigating different glioma entities. Indicated are mean and SD.

Identification of lncRNAs suitable as normalisers in studies investigating glioma and normal brain tissue. We identified 4 lncRNAs that show stable expression in different glioma entities and in normal white matter. These normalisers can be regarded as universal normalisers that are suitable as references in a broad range of lncRNA studies. Indicated are mean and SD.

Stably expressed lncRNAs suitable for studies in human gliomas and normal brain tissue. We identified 4 lncRNAs that show stable expression levels in all three glioma entities and in normal occipital white matter. These lncRNAs may be regarded as universal normalisers applicable in a broad range of lncRNA studies. All lncRNAs are arranged according to their stability values. Intragroup and intergroup variations indicated were calculated using the NormFinder algorithm.

| Glioma and white matter | Intragroup variation | Intergroup variation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene name | Stability value | A II | A III | GBM | WM | A II | A III | GBM | WM |

| HOXA6as | 0.019 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.001 | -0.002 | 0.003 | -0.004 | 0.002 |

| H19 ups. cons. 1, 2 | 0.024 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | -0.025 | -0.002 | 0.012 | 0.014 |

| Zfhx2as | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.000 | -0.015 | -0.020 | -0.003 | 0.038 |

| BC200 | 0.044 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.042 | 0.018 | -0.005 | -0.055 |

Discussion

Recently it has been found that mRNA represents only a small fraction of RNA as the vast majority of DNA is transcribed into RNAs. In this context, lncRNAs are of emerging importance as there is increasing evidence that lncRNAs are of regulatory significance in numerous cellular processes [1, 4-7]. Since conscious quantifications of lncRNAs need adequate, reliable normalisation strategies, it is important to perform systematic evaluations of potential normalisers [42, 43].

The current study is the first systematic analysis of a wide range of lncRNAs in gliomas of different WHO-Grades (diffuse astrocytoma WHO-Grade II, anaplastic astrocytoma WHO-Grade III, glioblastoma WHO-Grade IV) as well as normal white matter using quantitative PCR (qPCR) to identify suitable normalisers allowing both longitudinal studies of gliomas before and after malignant transformation and studies comparing glioma and normal brain tissue. Investigating 90 lncRNAs being annotated in the lncRNA database [9] we were able to detect suitable references for the different tumour entities both alone and in comparison with each other. Of the 90 lncRNAs we identified 24 suitable normalisers in diffuse astrocytomas, 22 in anaplastic astrocytomas and 12 in glioblastomas. Interestingly, we found that glioblastoma showed the lowest number of stably expressed lncRNAs. Applying a rigorous bioinformatical approach, the number of suitable normalisers was dramatically reduced by comparing expression levels across all three glioma entities: We identified 7 suitable normalisers for studies comparing different glioma entities (i.e. Zfhx2as, SNHG4, HOXA6as, H19 upstream conserved 1 and 2, ncR-uPAR, 21A and BC200). These normalisers are suitable for e.g. longitudinal studies of gliomas before and after malignant transformation. Interestingly, even highly ranked in single tumour entities many lncRNAs turned out to be unsuitable as normalisers across tumour subgroups as being differentially expressed in different entities and thus not being suitable as proper intergroup normalisers. The addition of normal white matter resulted in only 4 suitable normalisers: HOXA6as, H19 upstream conserved 1 and 2, Zfhx2as and BC200. Thus, these 4 normalisers may be regarded as universal normalisers suitable for a broad range of lncRNA studies. SNHG4, ncR-uPAR and 21A showed to be differentially expressed in glioma and normal white matter being unsuitable as normalisers comparing normal tissue and glioma. As recent publications show that normalisation to a single reference gene is not sufficient, even if normalisers were identified in a conscious way, the optimal normalisation strategy should include at least a combination of two or more references [37, 44, 45]. Thus, we suggest a combination of all 4 universal normalisers in lncRNA studies. This strategy will further increase the reproducibility and validity of lncRNA studies in glioma and normal brain tissue.

In summary, we showed that the proper selection of normalisers is an absolute requirement for valid determination of lncRNA expression profiles using quantitative PCR. Only by selecting proper normalisers, valid and reproducible data can be generated. We identified a set of 4 normalisers applicable as references for accurate lncRNA studies in human diffuse astrocytoma (WHO-Grade II), anaplastic astrocytoma (WHO-grade III), glioblastoma (WHO-Grade IV) and normal white matter tissue. A combination of these 4 normalisers will result in unbiased results. Thus, the data presented in this study will further boost research on lncRNAs in human gliomas and allows even longitudinal studies of gliomas during malignant transformation and tumour progression.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Neurobiobank Munich for providing control tissue for this study.

Competing Interests

None declared.

References

1. Bu D, Yu K, Sun S, Xie C, Skogerbo G, Miao R. et al. NONCODE v3.0: integrative annotation of long noncoding RNAs. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:D210-5 doi:10.1093/nar/gkr1175

2. He S, Liu C, Skogerbo G, Zhao H, Wang J, Liu T. et al. NONCODE v2.0: decoding the non-coding. Nucleic acids research. 2008;36:D170-2 doi:10.1093/nar/gkm1011

3. Liu C, Bai B, Skogerbo G, Cai L, Deng W, Zhang Y. et al. NONCODE: an integrated knowledge database of non-coding RNAs. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33:D112-5 doi:10.1093/nar/gki041

4. Mattick JS, Amaral PP, Dinger ME, Mercer TR, Mehler MF. RNA regulation of epigenetic processes. BioEssays: news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2009;31:51-9 doi:10.1002/bies.080099

5. Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nature reviews Genetics. 2009;10:155-9 doi:10.1038/nrg2521

6. Wilusz JE, Sunwoo H, Spector DL. Long noncoding RNAs: functional surprises from the RNA world. Genes & development. 2009;23:1494-504 doi:10.1101/gad.1800909

7. Taft RJ, Pang KC, Mercer TR, Dinger M, Mattick JS. Non-coding RNAs: regulators of disease. The Journal of pathology. 2010;220:126-39 doi:10.1002/path.2638

8. Kapranov P, Cheng J, Dike S, Nix DA, Duttagupta R, Willingham AT. et al. RNA maps reveal new RNA classes and a possible function for pervasive transcription. Science. 2007;316:1484-8 doi:10.1126/science.1138341

9. Amaral PP, Clark MB, Gascoigne DK, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. lncRNAdb: a reference database for long noncoding RNAs. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39:D146-51 doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1138

10. Ma L, Bajic VB, Zhang Z. On the classification of long non-coding RNAs. RNA biology. 2013 10

11. Lee JT, Bartolomei MS. X-inactivation, imprinting, and long noncoding RNAs in health and disease. Cell. 2013;152:1308-23 doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.016

12. Clemson CM, McNeil JA, Willard HF, Lawrence JB. XIST RNA paints the inactive X chromosome at interphase: evidence for a novel RNA involved in nuclear/chromosome structure. The Journal of cell biology. 1996;132:259-75

13. Lee JT, Davidow LS, Warshawsky D. Tsix, a gene antisense to Xist at the X-inactivation centre. Nature genetics. 1999;21:400-4 doi:10.1038/7734

14. Penny GD, Kay GF, Sheardown SA, Rastan S, Brockdorff N. Requirement for Xist in X chromosome inactivation. Nature. 1996;379:131-7 doi:10.1038/379131a0

15. Marahrens Y, Panning B, Dausman J, Strauss W, Jaenisch R. Xist-deficient mice are defective in dosage compensation but not spermatogenesis. Genes & development. 1997;11:156-66

16. Zhao J, Ohsumi TK, Kung JT, Ogawa Y, Grau DJ, Sarma K. et al. Genome-wide identification of polycomb-associated RNAs by RIP-seq. Molecular cell. 2010;40:939-53 doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.011

17. Zhao J, Sun BK, Erwin JA, Song JJ, Lee JT. Polycomb proteins targeted by a short repeat RNA to the mouse X chromosome. Science. 2008;322:750-6 doi:10.1126/science.1163045

18. Thorvaldsen JL, Bartolomei MS. SnapShot: imprinted gene clusters. Cell. 2007;130:958. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.033

19. Nie L, Wu HJ, Hsu JM, Chang SS, Labaff AM, Li CW. et al. Long non-coding RNAs: versatile master regulators of gene expression and crucial players in cancer. American journal of translational research. 2012;4:127-50

20. Prensner JR, Chinnaiyan AM. The emergence of lncRNAs in cancer biology. Cancer discovery. 2011;1:391-407 doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0209

21. Wu L, Murat P, Matak-Vinkovic D, Murrell A, Balasubramanian S. Binding interactions between long noncoding RNA HOTAIR and PRC2 proteins. Biochemistry. 2013;52:9519-27 doi:10.1021/bi401085h

22. Tang L, Zhang W, Su B, Yu B. Long noncoding RNA HOTAIR is associated with motility, invasion, and metastatic potential of metastatic melanoma. BioMed research international. 2013;2013:251098. doi:10.1155/2013/251098

23. Hu W, Alvarez-Dominguez JR, Lodish HF. Regulation of mammalian cell differentiation by long non-coding RNAs. EMBO reports. 2012;13:971-83 doi:10.1038/embor.2012.145

24. Wang KC, Yang YW, Liu B, Sanyal A, Corces-Zimmerman R, Chen Y. et al. A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nature. 2011;472:120-4 doi:10.1038/nature09819

25. Kotake Y, Nakagawa T, Kitagawa K, Suzuki S, Liu N, Kitagawa M. et al. Long non-coding RNA ANRIL is required for the PRC2 recruitment to and silencing of p15(INK4B) tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene. 2011;30:1956-62 doi:10.1038/onc.2010.568

26. Yao J, Zhou B, Zhang J, Geng P, Liu K, Zhu Y. et al. A new tumor suppressor LncRNA ADAMTS9-AS2 is regulated by DNMT1 and inhibits migration of glioma cells. Tumour biology: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2014;35:7935-44 doi:10.1007/s13277-014-1949-2

27. Zhang XQ, Leung GK. Long non-coding RNAs in glioma: Functional roles and clinical perspectives. Neurochemistry international. 2014;77C:78-85 doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2014.05.008

28. Chistiakov DA, Chekhonin VP. Extracellular vesicles shed by glioma cells: pathogenic role and clinical value. Tumour biology: the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2014;35:8425-38 doi:10.1007/s13277-014-2262-9

29. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A. et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta neuropathologica. 2007;114:97-109 doi:10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4

30. Crocetti E, Trama A, Stiller C, Caldarella A, Soffietti R, Jaal J. et al. Epidemiology of glial and non-glial brain tumours in Europe. European journal of cancer. 2012;48:1532-42 doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2011.12.013

31. Dolecek TA, Propp JM, Stroup NE, Kruchko C. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2005-2009. Neuro-oncology. 2012;14(Suppl 5):v1-49 doi:10.1093/neuonc/nos218

32. Klatte M, Bauer P. Accurate Real-time Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR. Methods in molecular biology. 2009;479:61-77 doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-289-2_4

33. Nolan T, Hands RE, Bustin SA. Quantification of mRNA using real-time RT-PCR. Nature protocols. 2006;1:1559-82 doi:10.1038/nprot.2006.236

34. Tricarico C, Pinzani P, Bianchi S, Paglierani M, Distante V, Pazzagli M. et al. Quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction: normalization to rRNA or single housekeeping genes is inappropriate for human tissue biopsies. Analytical biochemistry. 2002;309:293-300

35. Langnaese K, John R, Schweizer H, Ebmeyer U, Keilhoff G. Selection of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in a rat asphyxial cardiac arrest model. BMC molecular biology. 2008;9:53. doi:10.1186/1471-2199-9-53

36. Bustin SA, Beaulieu JF, Huggett J, Jaggi R, Kibenge FS, Olsvik PA. et al. MIQE precis: Practical implementation of minimum standard guidelines for fluorescence-based quantitative real-time PCR experiments. BMC molecular biology. 2010;11:74. doi:10.1186/1471-2199-11-74

37. Bustin SA. Why the need for qPCR publication guidelines?--The case for MIQE. Methods. 2010;50:217-26 doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.12.006

38. Kraus TF, Globisch D, Wagner M, Eigenbrod S, Widmann D, Munzel M. et al. Low values of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), the "sixth base," are associated with anaplasia in human brain tumors. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2012;131:1577-90 doi:10.1002/ijc.27429

39. Thon N, Eigenbrod S, Grasbon-Frodl EM, Lutz J, Kreth S, Popperl G. et al. Predominant influence of MGMT methylation in non-resectable glioblastoma after radiotherapy plus temozolomide. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2011;82:441-6 doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.214593

40. Thon N, Eigenbrod S, Grasbon-Frodl EM, Ruiter M, Mehrkens JH, Kreth S. et al. Novel molecular stereotactic biopsy procedures reveal intratumoral homogeneity of loss of heterozygosity of 1p/19q and TP53 mutations in World Health Organization grade II gliomas. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2009;68:1219-28 doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181bee1f1

41. Andersen CL, Jensen JL, Orntoft TF. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: a model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5245-50 doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0496

42. Gao Q, Wang XY, Fan J, Qiu SJ, Zhou J, Shi YH. et al. Selection of reference genes for real-time PCR in human hepatocellular carcinoma tissues. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2008;134:979-86 doi:10.1007/s00432-008-0369-3

43. Durrenberger PF, Fernando FS, Magliozzi R, Kashefi SN, Bonnert TP, Ferrer I. et al. Selection of novel reference genes for use in the human central nervous system: a BrainNet Europe Study. Acta neuropathologica. 2012;124:893-903 doi:10.1007/s00401-012-1027-z

44. Abdel Nour AM, Azhar E, Damanhouri G, Bustin SA. Five years MIQE guidelines: the case of the Arabian countries. PloS one. 2014;9:e88266. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088266

45. Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M. et al. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clinical chemistry. 2009;55:611-22 doi:10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Theo F. J. Kraus, Center for Neuropathology and Prion Research (ZNP), Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Feodor-Lynen-Str. 23, D-81377, Munich, Bavaria, Germany. Tel: +49/(0)89/2180-78021; Fax: +49/(0)89/2180-78037; Email: theo.krausuni-muenchen.de.

Corresponding author: Theo F. J. Kraus, Center for Neuropathology and Prion Research (ZNP), Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Feodor-Lynen-Str. 23, D-81377, Munich, Bavaria, Germany. Tel: +49/(0)89/2180-78021; Fax: +49/(0)89/2180-78037; Email: theo.krausuni-muenchen.de.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact